In southwest Ohio, about a mile from the Indiana state line, a long-forgotten town with a special place in African American history is struggling to be reborn.

Longtown was established nearly 200 years ago in what is now Greenville. The settlement grew into a thriving mixed-race community and a major stop on the Underground Railroad.

Now, descendants of those pioneering settlers are working to bring Longtown back to life for others to experience.

Longtown’s Founding

In 1818, James Clemens, a freed slave from Rockingham County, Virginia, settled in Darke County, Ohio, with his wife Sophia Sellers and their five children, and began to farm.

“They were the sons and daughters of slave masters,” says historian and Longtown descendant Roane Smothers.

Smothers says some slave owners not only acknowledged the children they bore with slaves but also provided them with financial support. Such was the case with James and Sophia, who purchased land in Ohio with the help of Sellers' father, he says.

Longtown has been a passion for Smothers for more than a decade. In 2001 he got the settlement listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

While Longtown is mostly known today as an early African American settlement, from the beginning, Smothers says, it was a mixed-race community. Whites and Native Americans also called Longtown home.

“The Quakers left the south also because of their displeasure with slavery, and so you had African American farmers living next door to Quakers or abolitionists,” Smothers says.

The original Clemens family farm eventually grew into the settlement later called Longtown. Clemens also established a church and a school, where Longtown residents worshipped and educated their children.

The settlement also included the Union Literary Institute, a school of higher education for students of any race.

The school was built on the Indiana-Ohio state line in the early 1800s. Its goal was "to provide for the high and noble purpose of carrying knowledge and learning within the reach of those who desire it."

A Forgotten Piece Of History

Historians theorize Longtown’s location was strategic - established close to the Ohio state line, so settlers could escape across the border if slavery laws changed.

Despite the relative racial harmony in Longtown, Ohio was still be a dangerous place for African Americans. In the early 1800s, state law severely restricted where and how African Americans could live and participate in society.

It is worth noting that Longtown’s establishment happened more than 50 years before President Abraham Lincoln would issue the Emancipation Proclamation, on January 1, 1863, freeing all slaves in border states.

Smothers says adding to Longtown’s rich racial makeup were free people of color from eastern states who felt threatened by slavery, and whites who opposed slavery, “so they had something in common, the belief of a community."

To Smothers, Longtown represents a forgotten piece of African American history. He says it wasn’t only during the Great Migration of the 1900s, or through the Underground Railroad, that African Americans made their way to the Midwest region.

“Sorry,” he says. “These people ran the Underground Railroad. They helped other escaped slaves go north to Canada. No, there were free people of color that existed here [and] worked the land, and James Clemens became a very successful farmer.”

Smothers says historians have documented more than 120 similar African American settlements in Ohio and Indiana.

Telling Their Story

On a rainy spring afternoon in April, a large tour bus pulls up to the old Clemens farmhouse. Some 50 history buffs exit the bus just as a thunderstorm breaks overhead.

Toting rain-hats and umbrellas, the tourists quickly make their way into the farm house to hear the story of Longtown. It’s one of three stops they’ve made on their trip from Indiana.

Entering the old farmhouse through a small screened-in patio, the visitors pack into an interior room to hear Smothers tell the story.

Longtown’s history is worth telling, Smothers says. He’s working hard to secure the funds needed to restore the Clemens house. So far, he's secured several restoration grants. The historian proclaims, “we're almost there.”

And he’s getting some help from another Longtown descendant, a young man named Connor Kaiser.

Connor grew up near Longtown in Greenville, Ohio. He's the Clemens' great-great-great-great-great grandson.

We met at the Bethel Long Wesleyan Church. It was built in 1936 but it’s had an active congregation since 1856. It’s the only remaining Longtown church.

Sitting in a pew at the back of the room, Connor reflected on his research into Longtown’s history, and his experiences growing up in a multigenerational mixed-race family.

“I don’t know that anything ever really clicked that I have colored people in my family,” he says. “We would go to grandma's house and there are cousins a lot darker than myself and we’d just play together like nothing. And so I guess I didn’t really learn it… it just was.”

Upon meeting Connor, most people would likely describe him as white. He’s pale-skinned, with blue eyes. And while some people might balk at his use of the outdated term “colored people” to describe his relatives, that’s exactly how Connor and his family describe themselves, he says.

“My great grandfather, he’s not living anymore, but he used to always want to be called colored and not Negro or Black because he wasn’t only African American," Connor says. "So, knowing where he came from he wanted to include all aspects of his racial mix, just like I do.”

Carrying On The Heritage

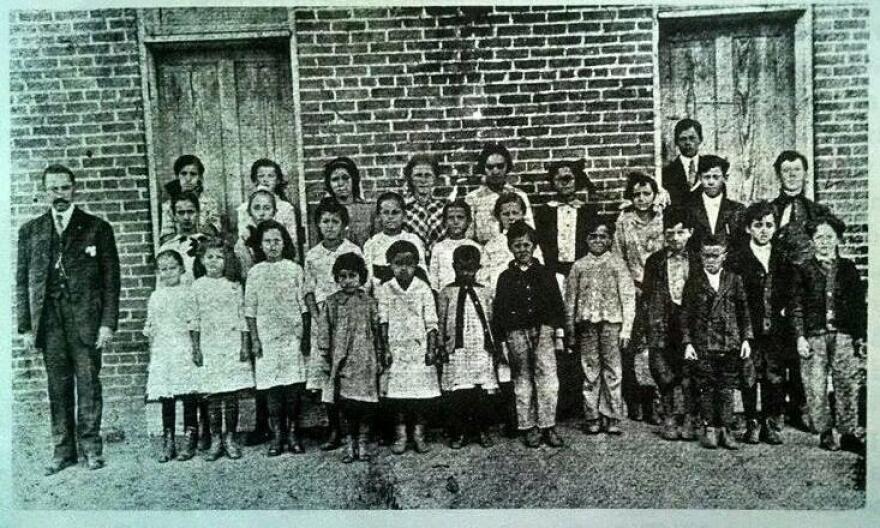

Decades of family photos show generations of Clemens family descendants, dark or light-skinned brothers and sisters standing next to their dark or light-skinned siblings, parents, aunts, uncles and cousins.

Connor says he’s proud of his heritage and the family he comes from. And he hopes to share his Longtown research with his own children someday.

Connor is currently a student at Wright State University. He’s in the International Studies program, with a focus on Middle Eastern studies.

But, he says, hometown is still close to his heart.

A few years ago he joined Roane Smothers in the efforts to preserve and further establish Longtown’s place in Ohio's history.

Smothers is glad to have the help and commends the young student for embracing his ancestors. He hopes others will follow but believes descendants of other mixed-raced communities like Longtown have buried their non-white pasts or don't know about them.

Connor and Smothers hope to one day open the Clemens historic family homestead, and other nearby sites, as a museum dedicated to telling the story of Longtown and the generations of families who lived there.