I knew of Eugene Drucker as a formidable violinist, and as a member of the acclaimed Emerson String Quartet. The Emersons have been established internationally for years. And they've long had a home on Classical 101.

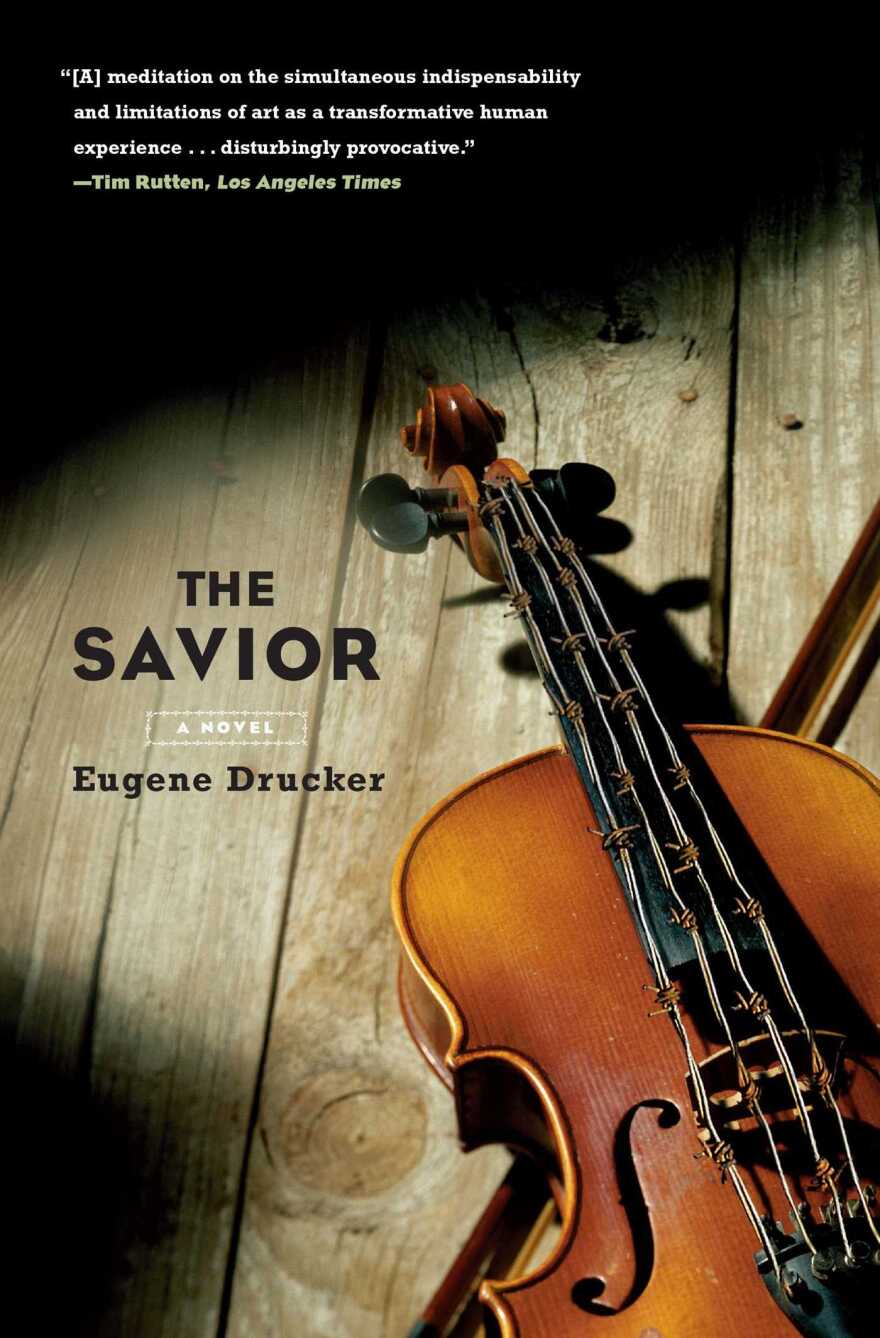

But I admit to being surprised to read that Drucker wrote a novel in 2007, The Savior. This is certainly no Mozart in the Jungle sex with the maestro tome.

I read about Drucker's novel over at Slipped Disc. Administered by British cultural pundit and bad boy Norman Lebrecht — a very witty and bright provocateur and a novelist himself — Slipped Disc bills itself as "the inside track on classical music and related cultures."

If you want to know who's been fired, who's getting a pricey divorce, who won this competition and who should have won that competition, then Slipped Disc is for you. It's sort of a Real Housewives of Paris, London, Vienna, Rome and Dubuque.

Slipped Disc also hosts the Fortnightly Music Book Club. Discussions about The Savior are ongoing.

Toward the end of World War II, German violinist Gottfried Keller is forced to play for a literally captive audience in an extermination camp. The Commandant wants to experiment — what happens when prisoners surrounded by abuse and death are offered hope? And is music, specifically Bach, that hope?

Keller plays his violin to a room full of prisoners in the most appalling surroundings. Historically we know that those forced onto and off of the trains at Auschwitz and Dachau were met by orchestras playing light classics as they were herded into the gas chambers.

Keller's "concerts" are personal and intimate: one man, one violin and 20 or 30 people numbed by despair. Some are catatonic. Some dare to respond gently. A listener whispers for him to stop — don't play anymore. And a young woman insists Keller face up to the reality of his surroundings.

At the end, of course, no one is saved — least of all Keller.

I give Drucker a lot of credit for writing on such a horrendous subject without taking the easy way out.

The Commandant is too slick, too banal to be an obvious monster. Keller could have walked out, but is told that the Gestapo would be right after him. He stays.

Flashbacks show us Keller as a music student with a Jewish best friend, who is eventually not allowed to play in public.

There's a love affair with a fellow student whose father is recruiting Jewish artists for the orchestra formed by Bronislaw Huberman that became the Israel Philharmonic. It's even suggested that the Gentile Keller forge papers proving a Jewish grandparent — fatal in Nazi Germany, but seen as a possible way to a life in Palestine.

It doesn't happen. There's no redemption here. There's not an ending, but a pause as readers — and reality — try to grieve the horrors, and move forward.