Richard Nixon's second inauguration, on Jan. 19, 1973, featured a starry concert at the then-new Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The Philadelphia Orchestra—then and now among the world's finest—conducted by Eugene Ormandy, performed Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in a minor, with Van Cliburn, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture.

It's worth noting Ormandy, who had been music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra since 1936, was born in 1899 in Hungary. The immigrant and celebrated conductor led a premiere American orchestra for over 40 years.

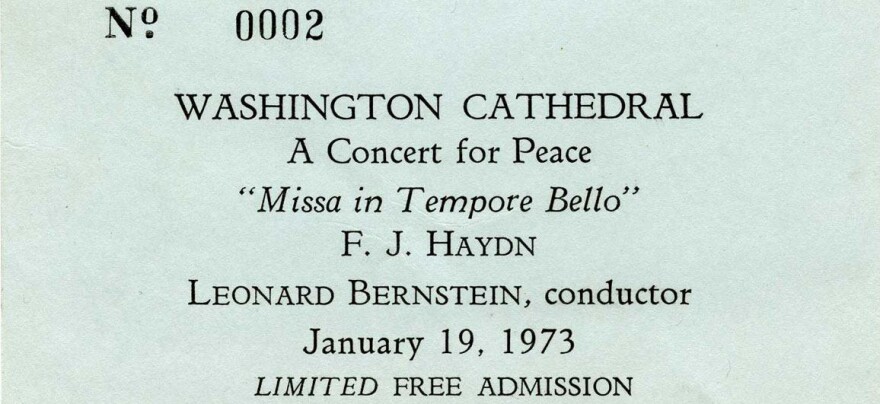

A mile away at the Washington National Cathedral, around the time Ormandy began conducting the Grieg concerto at the Kennedy Center, Leonard Bernstein walked off the high altar and stood in front of a pick-up orchestra, Norman Scribner's choir, and a dazzling quartet of vocal soloists: Patricia Wells, Gwendolyn Killebrew, Michael Devlin and Alan Titus.

Bernstein conducted only one work, Joseph Haydn's Missa in tempore belli "Mass in Time of War," for a jam-packed cathedral—3,000 people inside, another 10,000 standing outside in the rain.

The "tempore belli," or "time of war," Haydn referenced was the 1796 Austrian mobilization in response to the political unrest in France following the French Revolution.

The performance was televised by CBS, not for Haydn, but for Bernstein, President Nixon and the Vietnam War.

"While Cathedral officials were busy pointing out last week that the [Haydn’s] Mass [In Time of War] conducted by Leonard Bernstein was not 'counter' to anything, its function as a rallying point of anti-Nixon dissent was not lost on anybody. … In case any didn’t get the message … it was introduced by former Senator Eugene McCarthy, poet and early leader of the peace movement. The curate of St. John’s Episcopal Church went so far as to proclaim, 'Of course this is a protest. You don’t think all of those people are out there to hear the music, do you?' " —Washington Post, Jan. 20, 1973

There have been other times as divisive as these. But in living memory, 1968, with the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, through the final withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam in 1973, was an exceptionally bloody, chaotic time. Flower children and fire bombs—it was a period of great tragedy and unrest.

I won't tell you that Bernstein's performance of Haydn's Mass was meant to be entertaining or comforting. It was, pure and simple, a political gesture. It did not bring together people from all walks of life. But it did tell the world that Americans had had enough of wars in faraway lands and the stop-start-stop national civil rights efforts, and was an electorate only just beginning to recover from the assassinations of 1968.

Six months after this concert in the National Cathedral, 'Watergate" entered the national vocabulary.

But that's another story.