Maureen Charles is 66, an Air Force vet, a mother, a grandmother and a lifelong Cantonian. A woman whose neat handwriting fills the margins of her Bible.

She is not a convicted felon. Not anymore.

Three years ago, Gov. Mike DeWine launched the Expedited Pardon Project, designed to shave years off the normal pardon process. The bar to qualify is high, including at least 10 years free of prison, parole or probation.

Only about three dozen people have received the pardons so far. Charles is one of them.

Her pardon reads, “WHEREAS after careful consideration of all relevant factors, I, Mike DeWine, governor of the State of Ohio, have concluded that a full and unconditional pardon is warranted.”

She touches the gold seal, affixed to the pages of official whereases and therefores that wiped her legal slate clean of drug and prostitution charges.

She received word the pardon was on its way 30 years after her last arrest.

“I got a call from the governor’s office… and when I got that call, it was like getting a call from heaven,” Charles said. “It just gave an official freedom to all of that, just letting go. Being able to exhale.”

She’d been holding her breath for going on 35 years. That’s when we first met, and crack cocaine had largely extinguished her easy laugh and buried her artistic talent. She was a whip-thin figure going by the street name “Slim.” Her two older children were estranged; her toddler in foster care. Barefoot, she stole shoes. Needing a fix, she sold herself.

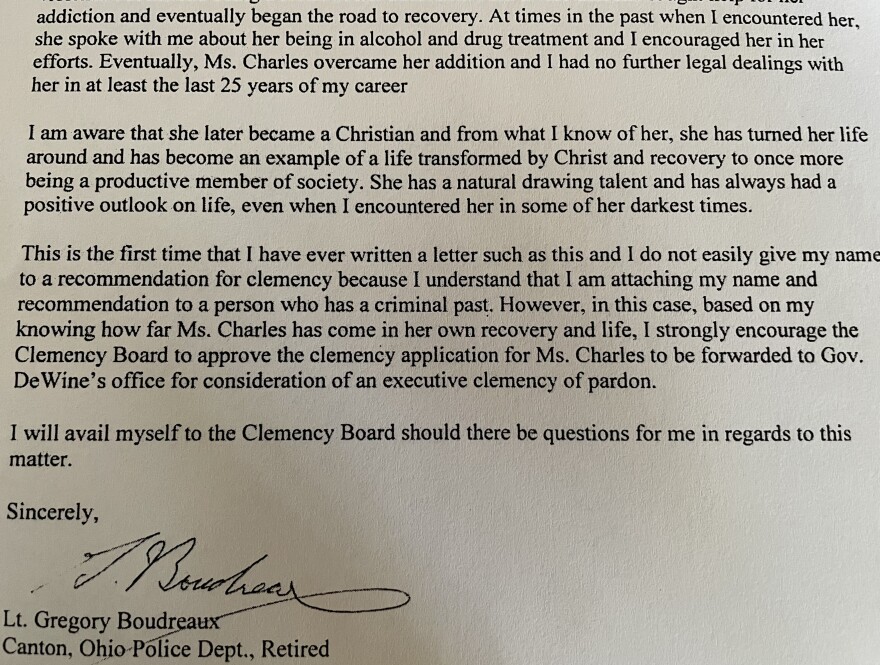

But even when she was in the back of a police cruiser heading to jail, now-retired Canton Police Lt. Greg Boudreaux remembered her spark.

“I thought she had a lot of potential. She was always very personable,” Boudreaux said. “I never knew her to be involved in crimes of violence or anything like that. And generally, you try to encourage people to reform their lives, get their lives together.”

Maureen’s “official” story

The state of Ohio’s official story of Maureen Charles ends in 1992, with nearly a dozen felony arrests for prostitution, drugs, theft and resisting arrest. For decades, that’s the story that showed up in background checks with no hint of what followed.

“Not just rehabilitated, I think it’s deeper than that,” she said. “I’ve been transformed.”

Charles last used crack in 1994, she said. She moved into the YWCA, got a job, regained custody of her son, Jordan, and reunited with her older children, Angel and Tina. She moved into a home built with Habitat for Humanity, and set up a children’s ministry in the basement. Mission trips to Jamaica and Ghana followed, as well as assisting a family from Togo to navigate the political asylum process in the United States.

If you ask how, she answers “prayer” — not one prayer, but many.

“I’m able to live life on life’s terms,” she said. “And with God’s help, I know I’m never alone.”

Still, some doors remained firmly closed.

No matter how old a record, she was blocked from certain jobs – even volunteering with youth organizations or with addicts in prison.

So, she decided to try to change the terms.

Working with the University of Akron — one of the first partners in the expedited pardon program — she began to assemble the pile of paperwork the process requires. It wasn’t easy.

DeWine launched the program in December 2019. A few months later, the coronavirus pandemic shut down just about everything, including court and police record rooms.

But Charles acknowledged another reason for the delays. Sometimes, she said, reliving the person she was just hurt too much.

“Something that you want really bad is to be redeemed from the past of your mistakes,” she said. “It was like looking in the mirror and feeling all that pain and frustration. And it took me back to the past, and I’m like, ‘Yuck, I don’t like what I’m feeling.’”

She pushed the paperwork aside. But she kept coming back. And ultimately, she said, the two-year process became a kind of therapy.

“Realizing where you’re at and who you are as a person, it took that to clean up the garbage, the residue,” Charles said. “It was like having an opportunity to wash that away.”

The path towards an expedited pardon

Last fall, Joann Sahl at the University of Akron School of Law called with word that Charles was scheduled for a hearing before the Adult Parole Authority, whose recommendation would be key in the governor’s decision.

It nearly didn’t happen. Charles got COVID-19. Sahl worried whether she could withstand such a high-stakes hearing – even by Zoom. Charles pleaded; they practiced and decided to go ahead. Then, five minutes before the hearing, Charles' internet cut out. She dashed to a friend’s house in a panic. But when the hearing began, “lo and behold, everything came together and it was just amazing,” she recalled.

The parole board voted 10-0 to recommend the pardon, and on March 28, the governor agreed.

One of a handful

Charles is one of just 37 people who have received the expedited pardons so far. Another 125 are somewhere in the process. Last year, the state expanded the effort with additional funding and law school partnerships.

“I believe that those who committed certain felony offenses in the past should not pay for their mistakes forever,” DeWine said in his pitch for support of the expedited pardon project.

But the project also has rejected nearly 200 people for a variety of reasons. Some had committed crimes that automatically exclude them such as homicide and sexual assault. Many didn’t have the 10-year clean record that the pardons require, or they couldn’t demonstrate a work record, community service and other outward signs of reform.

Charles understands the restrictions but thinks about younger people for whom 10 years is most of their adult lives. Meanwhile, she watches them run into walls, including job offers never extended or quickly rescinded after a background check.

“I know for a fact that they have really changed, and they’re doing positive things,” she said. “They’re working as best they can, but they’re qualified to have better jobs and to make better wages and to be able to take better care of themselves and their children.”

Life after the pardon

Outwardly, Charles' life has changed very little since her pardon.

She’s caring for three granddaughters, age five and under, in Texas while her widowed daughter is stationed in the Middle East. She celebrates the victories and frets about the challenges of her oldest son’s gourmet tea business in California. Jordan, the toddler she nearly lost custody of, is a software consultant in Columbus. They talk regularly. She calls him an old soul. He calls her heroic.

They used to talk occasionally about the pardon process as it stretched over two years. Jordan thinks of childhood friends with felony records who, based on time alone, don’t qualify for the program.

“But I know for a fact, if they were given a chance, they could succeed and they could make something out of that,” he said. “But I’m not the one they have to convince. They have to convince the people who are in charge of saying yes.”

Jordan appreciates how thorough the process was for his mom. The system, he said, simply can’t afford to get it wrong.

“They have to ensure that her story is accurate and her story is everything she says it is. Because if it wasn’t, that sort of damages the opportunity and potential of any individual that will come after her,” he said.

“You always hear individuals say, people can’t change,” Jordan said. “My mom, to me, has disproven that entirely.”

A new narrative

With her records sealed, the paperwork Maureen Charles worked so hard to track down no longer officially exists. In its place is a far more nuanced narrative.

It’s hers to share and she does, hoping others will see themselves in it.

Copyright 2022 WKSU. To see more, visit WKSU.