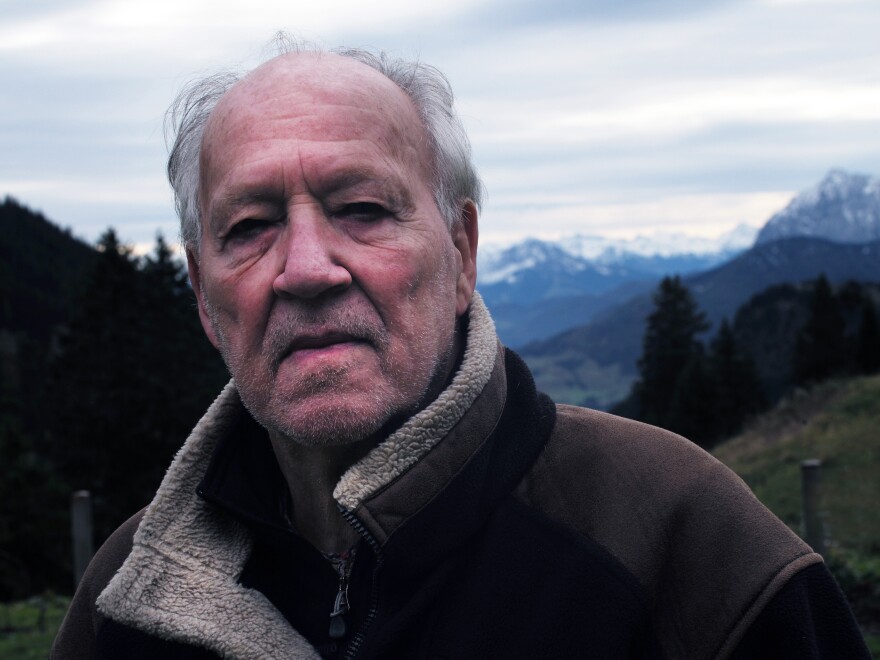

German filmmaker Werner Herzog's earliest memory is of war. He was 2 and a half in April 1945, and his mother woke him up in the middle of the night, wrapped him in blankets and rushed outside to watch the Allied airstrikes against the German city of Rosenheim, which was 40 miles away.

"The entire sky [was] pulsing slowly, red and orange," Herzog says. "I knew all of a sudden there is something out there. There's a world out there. There is war out there. There's a conflagration out there, and I became curious."

Herzog has traveled the world for decades, making movies about intense personalities and extreme conditions. His 1982 film Fitzcarraldo, which was shot in the Amazon jungle, tells the story of an European opera lover in Peru who tries to bring a steamship over a mountain. His 2005 documentary, Grizzly Man, followed a man who lived in Alaska among grizzly bears — until he was eaten by one.

Sometimes work has put Herzog in direct danger. He filmed the 2016 documentary Into the Inferno at the edge of an active volcano, where, he says, "blobs of lava came down on us, raining down — some of them very large, the size of a car, the size of a truck."

Despite the hazards, Herzog insists that he knows his own boundaries — and respects them.

"I'm a filmmaker, and I want to come back with a film and I want to come back alive because I want to edit the film and I want to show it to audiences," he says. But, he adds, "I think to look deep into our human nature, to look deep into the darkest recesses of our soul, the hidden things deep in our soul, you have to put human beings at some sort of an edge."

Now in his 80s, Herzog reflects on his unusual life and the curiosity that has fueled his career in the new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All. Just don't read it expecting a deep confessional: "I'm not into that business," he says. "I never liked too deep introspection."

Interview highlights

On what he realized after he stabbed his brother in the arm and leg over a pet hamster when they were kids

I knew that something like that cannot happen again. ... That shaped my character. And from one moment to the next, I knew you have to control what is wild in you. You have to be disciplined. And until today, 90% of what you see when you meet me is discipline. People think I'm the wild guy out there. No, I'm a disciplined professional.

On the mysterious clashes between brothers

We grew up with our mother, who raised us. We were three brothers and one mother. We lived in one single room in a sort of a boarding house. Of course, we had clashes like brothers would have. And until today, it's mysterious, foreign to us. Not long ago, a few years ago, I visited my older brother in Spain ... and we were at a fish restaurant and I studied the menu and he put his arm around my shoulder and all of a sudden I feel some stinging thing in my back and I smell smoke. And I realize he has set my shirt on fire with his cigarette lighter. And we laughed so hard and everybody around the table was appalled. But sometimes that's how brothers function and I love him dearly. And we do mischievous things to each other. It does happen. And it's not that serious. Somebody gave me his T-shirt and we cooled my back with a few glasses of Prosecco, and that was that.

On parodies of the sinister tone of his narration

I narrated my own writings, my own commentaries, and I had found my voice. But it's a stylized voice. When I'm talking to you, I'm talking like me in commentaries, there's a certain stylization, a certain performance in it, a certain hypnotic voice in it. ... It has caught on. Audiences love it, so I do it for them as well. ... But it's all performance. Don't ever believe I'm like that as a private person. ... [My wife] will testify that I am a mild-mannered, fluffy husband.

On why psychoanalysis is not his "thing"

It is not healthy if you circle too much around your own navel. And it is not good to recall all the trauma of your childhood. It's good to forget them. It's good to bury them. Not in all cases, but in most cases. So psychoanalysis is doing that. I do not deny that it is good and necessary in a very few cases. Yes, I admit it, but it's not my thing. But I keep telling men ... "Rather dead than going to a psychiatrist." But at the same time, "Rather dead than ever wearing a toupee." My hair is thinning and it's just accepted as it is. ... Women would immediately agree with me. You cannot live with a man who starts to wear a toupeeand thinks he's handsome now and rejuvenated.

I know who I am and I know where I come from. And I know where I'm heading towards. No fear and no regrets. Sure, I've made massive mistakes, and I'm, in a way, a result of my own defeats. So be it. They formed me. They made me think beyond what I normally thought before.

On feeling like he's the only "sane" person in Hollywood

I wouldn't have made some 80 films without having my wits together and my sanity and my professionalism. ... When you look at the craze of Hollywood and all these red carpet events in the statements at the red carpet ... it's all performative, borderline insanity in a way, saccharine, pink sort of vanilla-ice-cream emotions. I am the only one who is sane. ... Every single line in my memoirs shows you that I'm absolutely sane in an ocean of craze.

On growing up in war and postwar time

We were bombed out. There was a foot of glass shards and bricks and debris on my cradle when I was 14 days old. Of course, I grew up in postwar time – starvation, poverty. And since I had this experience, for me, it's obvious that there shouldn't be any war. I'm against any war at all. And of course, it is terrible what we are witnessing now [in the Middle East]. It is terrible. And it shouldn't be. And I hope it will come to a quick end.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.