Even before taking office, former President Donald Trump's administration obsessed over the U.S. census.

From a failed bid for a citizenship question to a presidential memo about unauthorized immigrants that was fast-tracked to the Supreme Court, its moves over the past four years followed a playbook first drawn up more than four decades ago by the Federation for American Immigration Reform.

In 1979, the hard-line group that became the most influential advocate for extreme restrictions on immigration launched a campaign that has held onto one consistent goal — obtaining an official count of unauthorized immigrants through the census to radically reshape Congress, the Electoral College and public policy.

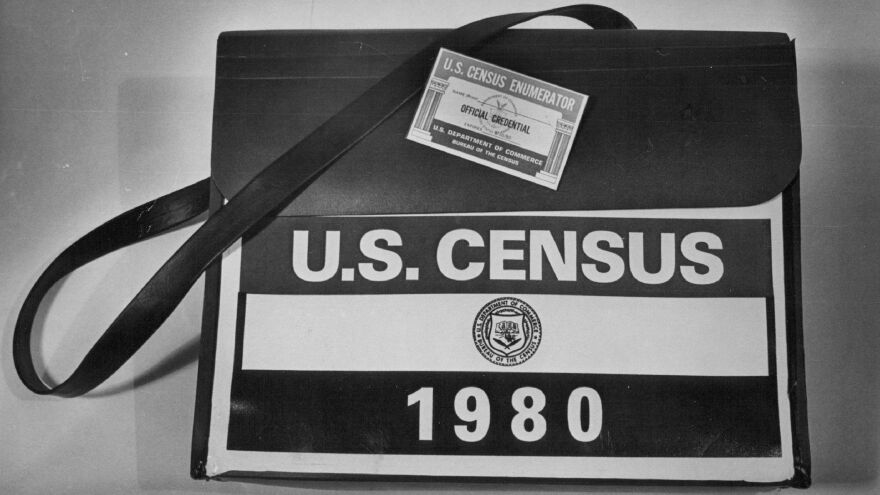

Starting with a lawsuit filed weeks before the official start of the 1980 census, FAIR documented its strategy in a paper trail that NPR has reviewed in the organization's archives at the George Washington University, as well as those of FAIR's founder at the University of Michigan.

"It's always been on the agenda," Dan Stein, FAIR's president, tells NPR, noting that it's "very possible" that, as early as November 2016, the group discussed with Trump officials the possibility of excluding unauthorized immigrants from a key set of 2020 census results.

To some, it may seem curious that part of Trump's agenda zeroed in on an often overlooked government tally of every person living in the U.S.

But census numbers hold what Trump has always wanted — power.

That power comes in the form of 435 votes in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. Once a decade, those votes are up for grabs among the states based on new census numbers. The more residents included in a state's population count, the more of a say it has for the next 10 years in how federal laws are made and how the next occupant of the White House is chosen.

The Constitution has spelled out specific instructions for the census. Not just citizens or voters, but "persons" who reside in the states are supposed to be counted. Congress eventually codified the 14th Amendment's language into federal law that calls for the "whole number of persons" living in each state and the "tabulation of total population" to be used when reapportioning House seats and electoral votes.

Census counting does have a thorny history. Before the Civil War, the fifth sentence of the country's founding document required an enslaved person to be counted as "three fifths" of a free person. And it was just before the 1940 census that the Census Bureau determined the phrase "excluding Indians not taxed" could no longer omit some American Indians from the apportionment counts.

But since the first U.S. head count in 1790, this has been an unwavering truth: No resident has ever been left out because of immigration status.

Trump officials attempted to break with that 230-year precedent. The administration, like FAIR, wanted to subtract unauthorized immigrants from the apportionment counts, taking power away from those residents and the communities where they live.

One of President Biden's first executive orders officially quashed the Trump memo that called for that extraordinary change.

But during the Trump years, FAIR came closer to getting that count of unauthorized immigrants than it has ever before.

A page out of an old playbook

The start of the Trump administration's four-year census saga centered around a hotly contested question: Is this person a citizen of the United States?

Trump officials wanted to use the census to directly ask for the citizenship status of every person living in every household in the country for the first time in U.S. history. That proposal has long been considered anathema to best practices for a complete and accurate head count, and the administration was not up front about exactly why it wanted to add the question to the 2020 census.

Many opponents of that citizenship question argued it was originally intended to depress census participation. Under federal law, no government agency or court can use personal information collected by the Census Bureau against anyone. But a long history of distrust of the census has made many noncitizens, Latinos, Asian Americans, and other historically undercounted groups wary of telling the government their household's citizenship status.

Some of the question's critics also pointed to a scheme concocted by a GOP redistricting mastermind, Thomas Hofeller, to use the neighborhood block-level citizenship data the question would generate to politically benefit Republicans and "Non-Hispanic Whites" in state and local elections for years to come.

To Roger Conner, who led FAIR until 1988 as the group's first executive director, it was clear that the Trump administration had another goal in mind — to change how congressional seats and electoral votes are reapportioned in order to curtail the political representation of areas where unauthorized immigrants live.

"I was saying to myself, 'This is perfectly obvious. Why can't someone figure out what's going on?' " Conner says, recalling the Trump administration's push for a citizenship question. "I assume that's because they thought it was not in their interest to let everybody know what their strategy was."

That strategy (which the administration never directly connected to apportionment until Trump's memo was released years later) began percolating through Trump's world even before he took office.

During the 2016 campaign, former Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach — an immigration hard-liner who has worked as a counsel to FAIR's legal arm and was described by FAIR's president as an "invaluable asset" to Trump's immigration team — discussed a census citizenship question with campaign officials.

Shortly after the inauguration in 2017, Kobach talked about the question with Trump, then-chief strategist Steve Bannon and then-chief of staff Reince Priebus, according to Kobach's testimony to congressional investigators.

Kobach later urged Wilbur Ross, the Trump-appointed commerce secretary overseeing the bureau, to add a specially-worded citizenship question to the census. It should also ask about immigration status, Kobach suggested in an email, so that the responses could address "the problem that aliens who do not actually 'reside' in the United States are still counted for congressional apportionment purposes."

Other internal emails released for the lawsuits over the question show that the reapportionment of congressional seats was top of mind for Ross shortly after taking over the Commerce Department. In a March 2017 message from fellow Trump appointee Earl Comstock with the subject line "Your Question on the Census," Ross received a link to a Census Bureau webpage that answered: "Are undocumented residents (aliens) in the 50 states included in the apportionment population counts?"

"Yes," the bureau's official response said.

But when Ross officially announced a citizenship question in 2018 as a late addition to the 2020 census form, it didn't come with Kobach's apportionment reasoning or checkboxes about immigration status. Instead, Ross used the Voting Rights Act to publicly justify the question, claiming the responses would help the Justice Department better enforce the civil rights era-law and protect "minority population voting rights."

More than a year later, the Supreme Court rejected that justification for appearing to be "contrived" and blocked the question from appearing on the 2020 census.

By that point, career civil servants at the Census Bureau had repeatedly warned Trump officials that adding the question would not only likely lower response rates in some areas, but also produce citizenship data less accurate and more expensive than what could be generated from government records.

After threatening to delay the census in the wake of his Supreme Court loss, Trump issued an executive order in July 2019 that directed other federal agencies to share their citizenship records with the Census Bureau, which was already under orders from Ross to use records to produce anonymized, block-level data about the U.S. citizenship status of every adult living in the U.S. that states could use for redistricting.

Buried within Trump's order about citizenship data was a new policy of developing "complete and accurate" data on "illegal aliens in the country" that did not attract much attention at the time. Existing estimates by the Department of Homeland Security and academic researchers, the order said, are not reliable enough to "evaluate" policy proposals about enforcing immigration laws and changing eligibility rules for public benefits.

"Data tabulating both the overall population and the citizen population could be combined with records of aliens lawfully present in the country to generate an estimate of the aggregate number of aliens unlawfully present in each State," said Trump's order, which Biden reversed last month.

At the White House Rose Garden announcement for Trump's directive, the then-head of the Justice Department, William Barr, made no direct mention of how the DOJ could use the data to enforce the Voting Rights Act. Instead, Barr made sure to highlight how the data "may be relevant" to a lawsuit filed in 2018 by the state of Alabama "over whether illegal aliens can be included for apportionment purposes."

FAIR's underground beginnings

These signals from the Trump administration echoed arguments FAIR first made more than 40 years ago.

Toward the end of the 1970s, FAIR was a fledgling advocacy group desperate to emerge from a windowless basement office in Washington, D.C., as a national voice.

The U.S. was more than a decade into major demographic shifts: A greater and greater share of people living inside the U.S. were born elsewhere, and a predominantly white population was becoming less so.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 had ended an earlier quota system that favored people from Northern and Western Europe, while also imposing the first caps on the number of people allowed to enter from Mexico and other countries in the Western Hemisphere. The landmark law, along with the end of a legal program for temporary farmworkers from Mexico, helped usher in a rise in immigration, both legal and illegal, from Latin America, Asia and other parts of the world.

That led John Tanton — an eye doctor from a mostly white resort town along Lake Michigan who held a particular interest in population control as a form of environmentalism — to start FAIR.

The group's calls for an end to illegal immigration and fewer legal pathways for newcomers were not met with fanfare.

"We were obviously very small fish in a very big pond, and so got little attention," Tanton later recalled in an oral history interview that touched on FAIR's early days working underground with less than a handful of staffers.

To try to make a splash, FAIR went to court in December 1979.

Its federal lawsuit against former President Jimmy Carter's administration called for a citizenship question to be included on both the long and short versions of the 1980 census form. The responses, FAIR argued, would generate a count of noncitizens that could eventually produce a state-by-state tally of unauthorized immigrants by matching noncitizens with green cards to government records.

Concerned about persistent undercounts, some census advocates at the time focused their energy on encouraging unauthorized immigrants to participate in the count.

Conner, FAIR's first executive director, recalls reading a 1979 newspaper article about that effort and says FAIR sued partly out of concern that including unauthorized immigrants in the apportionment counts would increase the political power of "institutions that would favor the perpetuation, the expansion of immigration."

Still, in a 1980 statement to the House Judiciary subcommittee on immigration, Conner wrote that while FAIR wants unauthorized immigrants excluded from apportionment, it also "supports and encourages a full and accurate counting of illegal immigrants in the 1980 Census."

"This is a difficult and perhaps impossible undertaking," Conner added, "but it should nevertheless be worthwhile to attempt to gather more accurate information than we now possess about the number and characteristics of illegal immigrants within the United States."

Finding lawyers in Washington willing to make FAIR's arguments in court, though, was not easy.

"I had to explain to them why limiting immigration was the right thing, and FAIR wasn't a racist group," Conner explained in a 1989 oral history interview documented in the organization's archives. "It was a lost cause."

"The language of the Constitution is not ambiguous"

FAIR's last-minute lawsuit eventually paid off in terms of media attention. It garnered a radio segment on NPR's Morning Edition and a front-page, below-the-fold story in The New York Times, among other news coverage.

But the case was tossed out of a lower court, and the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal. FAIR and the other plaintiffs did not have a right to sue, the three-judge panel of the lower court in D.C. ruled. And their case, the panel noted, appeared "very weak on the merits."

"The language of the Constitution is not ambiguous," the judges wrote in their opinion. "It requires the counting of the 'whole number of persons' for apportionment purposes, and while illegal aliens were not a component of the population at the time the Constitution was adopted, they are clearly 'persons.' "

Going back to the 1920s, the judges pointed out, there have been multiple attempts to leave unauthorized immigrants and other noncitizens out of the apportionment counts. But with no change to the country's founding document, they have all failed. Their opinion quotes the remarks of Rep. Emanuel Celler, a Democrat from New York, during a 1940 House debate over whether unauthorized immigrants could be omitted:

Sen. David Reed, a Republican from Pennsylvania, came to the same conclusion more than a decade earlier in the 1920s.

After the 1920 census, reapportioning House seats was so heated, in fact, that for the first time in U.S. history the process didn't happen at all that decade. The Republican majority of a mostly rural Congress stalled on the constitutional mandate, refusing to use numbers that confirmed the U.S. had become a predominantly urban nation.

Weeks before lawmakers passed the 1929 law that turned reapportionment into an automatic process after the 1930 count, Reed took part in a Senate debate over whether "aliens," including unauthorized immigrants, could be excluded from the counts.

Reed was a namesake and architect of the Johnson-Reed Act, also known as the Immigration Act of 1924 that was designed to suppress people from Eastern and Southern Europe, and completely stop people from Asia, from immigrating to the U.S.

"I disagree to the bottom of my heart," Reed emphasized on the Senate floor, with the Constitution's original framers and the 14th Amendment's drafters choosing to use the term "persons" in their apportionment instructions instead of "citizens" or "voters who actually have cast their votes at the last general election."

But Reed could not support a bill amendment for excluding unauthorized immigrants and other noncitizens because, the senator said, "the oath which we take to support the Constitution includes the obligation to support it when we dislike its provisions as well as when we are in sympathy with them."

"It is literally now or never"

Despite losing in the courts, FAIR tried to muster support for more legal action after its 1979 lawsuit.

Tanton, FAIR's founder, looked for donors to stand up a $50,000 a year litigation program. In a 1980 letter written to a potential funder before FAIR's appeal ended, Tanton said that if their census lawsuit failed, "illegals will have Representatives beholden to them, effectively foreclosing any chance of stemming their influx. It is literally now or never: the decision rests on those of us who understand the problem."

The census lawsuit was a tool for getting "middle America" to support FAIR's work, Tanton later explained in a 1981 letter to an attorney who helped start the group's litigation program, by showing them that immigration was a "problem" not just for states like Texas, California and Florida.

In the same letter, Tanton floated the possibility of also pushing for the exclusion of green card holders, who are authorized to permanently stay in the U.S., and carrying out "citizen-only reapportionment," which "would further sweeten FAIR's prospects by shifting seats away from areas where politicians are compromised by an immigrant constituency."

According to records in FAIR's archives, though, the group stayed focused on the exclusion of unauthorized immigrants. One of FAIR's attorneys tried to persuade the states of Indiana and Missouri, which each lost a vote in the House and Electoral College after the 1980 census, as well as Alabama and Georgia, to sue over the apportionment results, and Conner, FAIR's first executive director, worked on selling the idea to the organization's board of directors.

"This lawsuit, with a potential for altering the 1984 Presidential election, will garner an inordinate amount of publicity," Conner wrote in an internal memo that year, suggesting the attention would be "extremely useful as a device to shift the news media focus" toward "the problems caused by illegal migration" and away from criticism of a FAIR-backed proposal for sanctions against employers who hire unauthorized immigrants.

Even so, it would take four more years before FAIR filed its second lawsuit over census apportionment counts. In 1988, it challenged the administration of former President Ronald Reagan over its plans for the 1990 census. This time, FAIR was joined by the states of Alabama, Kansas and Pennsylvania, as well as a more high-profile lead plaintiff — U.S. Rep. Tom Ridge, the Republican congressman from Pennsylvania who later became the state's governor and the country's first homeland security secretary.

In an attempt to recruit lawmakers to their cause, FAIR targeted delegations from states that were projected to lose House seats if the apportionment counts were altered to leave out unauthorized immigrants. FAIR emphasized that if successful, the lawsuit would not hurt states' bottom lines. Unauthorized immigrants would still be counted in the census numbers used to guide the distribution of federal grants to states, just not in the counts for dividing up House seats and electoral votes.

But the outcome in court turned out the same: The case was dismissed without a trial.

Still, Tanton was not ready to give up. Months after that loss in 1989, Tanton wrote a letter to the head of FAIR's legal arm, the Immigration Reform Law Institute, about a news report on the likelihood of Michigan losing two House seats after the 1990 census.

"This stirs the pot," Tanton said, "and again makes me wonder about refiling the census suit[,] say from Michigan, after the results are announced and before apportionment takes place when the actual shift of seats will be known. How complex would this be?"

They knew they were not going to get it right away. They knew eventually that the tide would change.

"Trying to stop" the "browning of America"

The year before FAIR lost its second attempt to exclude unauthorized immigrants through the courts, Tanton came under public scrutiny. A 1988 article in The Arizona Republic revealed that he had denigrated Latinos and warned of a "Latin onslaught" in a memo written for an immigration conference.

"How will we make the transition from a dominant non-Hispanic society with a Spanish influence to a dominant Spanish society with non-Hispanic influence?" asked Tanton, who, until he died in July 2019, was listed on FAIR's website as a member of its national board of advisers. "As Whites see their power and control over their lives declining, will they simply go quietly into the night? Or will there be an explosion?"

"What they were trying to stop was the browning of America," says Arnoldo Torres, who was a vocal critic of FAIR's policies as the executive director of the League of United Latin American Citizens until 1985.

Among FAIR's policy positions — which over the years have included opposing pathways to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants and ending the 14th Amendment's guarantee of birthright citizenship — altering the census apportionment counts was "not the issue that they led off with," but was "always an undercurrent," Torres recalls. "This was not a passing fancy."

"They were in for the long haul. They knew they were not going to get it right away," Torres says. "They knew eventually that the tide would change."

In the meantime, FAIR developed plans to change the apportionment process and get a count of unauthorized immigrants through the two other branches of government, having so far failed in the courts. An internal report prepared for FAIR's board of directors in October 1987 called it a "three-pronged approach."

One strategy included lobbying Congress to require the Census Bureau to "differentiate illegal aliens from citizens and legal residents on its questionnaire" for the head count, Simin Yazdgerdi, FAIR's then-director of government relations, wrote in the report.

During an August 1987 strategy session, FAIR determined its legislative strategy "should be conducted quietly so that the courts would not be tempted to a) delay making a decision until Congress had acted; or b) use any negative legislative history (i.e., floor statements, testimony) against us," according to an internal memo by Yazdgerdi.

"Emphasize how Republicans will be hurt most by inclusion of illegal aliens," the memo specified about how to persuade the Reagan administration's Justice Department and Office of Management and Budget to "influence" the Census Bureau.

While FAIR may have expected a more receptive audience among GOP members, support for omitting unauthorized immigrants from apportionment did not fall neatly along party lines in the 1980s.

In fact, among the plaintiffs joining Rep. Ridge in FAIR's lawsuit before the 1990 census were House Democrats from Alabama, Connecticut, Kansas, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Before the suit was filed, Ridge and Democratic Rep. Barbara Kennelly of Connecticut spearheaded a 1987 House bill that called for excluding unauthorized immigrants and including U.S. military and civilian Defense Department employees stationed abroad, who at the time were not expected to be counted for apportionment.

In 1988, the Justice Department told lawmakers that it opposed the bill because excluding unauthorized immigrants from the apportionment counts, it concluded, is unconstitutional. "If it were passed, we would recommend that the President veto it," wrote then-Acting Assistant Attorney General Thomas Boyd, a Reagan appointee.

The House bill stayed stuck in committee, but it had bipartisan support, including from Democratic cosponsors from Georgia, Indiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio and Texas.

"It's hard to explain to people. The Democrats were aligned with organized labor [and] didn't want immigrants," says Antonia Hernández, who opposed FAIR on immigration policy as president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund for close to two decades beginning in 1985. MALDEF tried to intervene in FAIR's 1988 lawsuit to defend the inclusion of unauthorized immigrants in apportionment counts.

As for the third prong of FAIR's strategy, the group mapped out the possibility of a "favorable White House decision" that would instruct the Census Bureau to collect information on people's immigration status, according to the group's 1987 board report. But that path did not open until Trump became president 30 years later.

"The efforts have been clumsy"

After the 1990 census, FAIR shifted its focus toward Congress given its lack of headway in the courts and with presidential administrations.

"You don't want to involve yourself in quixotic efforts that are doomed to fail," says Stein, the group's president who first joined FAIR in 1982.

But FAIR's calculations changed after Trump won.

After entering office, the Trump administration put in place many hard-line immigration proposals long championed by FAIR and the network of organizations that grew from it — including cutting the number of refugees allowed to resettle in the U.S. down to historic lows. Former FAIR staffers, including Julie Kirchner, who became the ombudsman at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services after running FAIR for nearly a decade as its executive director, also joined the administration's ranks.

And they've been in such a hurry to do something, the efforts have been clumsy.

Though Trump's White House press office did not respond to NPR's questions about whether the administration consulted with FAIR on its push to exclude unauthorized immigrants from apportionment counts, Stein says: "It was certainly part of our legislative plan for the new administration back in November of 2016."

Hernández, MALDEF's former president, says that the lack of comprehensive immigration reform helped thrust the apportionment issue front and center during the Trump administration. "It's just gained steam and gained steam," Hernández says.

In the decades since its basement beginnings, FAIR has expanded into a suite of offices near the U.S. Capitol, across the street from the office of the USCIS director. FAIR's staff, including its legal arm, now totals 36, according to spokesperson Matthew Tragesser.

With the Trump administration in power, FAIR gained an invaluable advantage — a ready and willing partner inside the federal government during the final 2020 census planning stages.

"What they haven't been yet able to do through the courts, they've been able to do through the executive branch," Hernández says. "And they've been in such a hurry to do something, the efforts have been clumsy."

The administration's inconsistency was on full display during the citizenship question lawsuits. Public statements about Voting Rights Act enforcement fronted behind-the-scenes discussions about altering census numbers for House seat reapportionment.

A redacted August 2017 email appeared to foreshadow what became the administration's ultimate strategy — citing a 1992 Supreme Court ruling to argue that the president has the discretion to decide whether to include unauthorized immigrants in the apportionment counts.

"Ultimately, we do not make decisions on how the data should be used for apportionment, that is for Congress (or possibly the President) to decide," wrote then-Commerce Department attorney James Uthmeier. "I think that's our hook here."

Then, while testifying under oath about the citizenship question in 2018, Trump officials could not avoid bringing up apportionment.

John Gore — a Justice Department appointee at the time who testified that adding the citizenship question to census forms was not necessary for enforcing the Voting Rights Act — confirmed that when Jeff Sessions was U.S. attorney general, there was discussion at the highest levels of the DOJ about reapportioning House seats using "some other measure" than the total number of residents in each state.

Trump himself tied the push for a citizenship question to apportionment the same day the White House released the July 2020 presidential memo about excluding unauthorized immigrants. In a written statement, Trump said:

Some career Census Bureau officials suspected that Trump's memo helped drive the administration to suddenly direct the bureau to rush counting last summer and cut back on quality checks for the 2020 census results, a report by the Commerce inspector general's office revealed. The administration appeared desperate to get a hold of census results before the end of Trump's term in case Biden won the election.

Practical challenges

Despite posing serious threats to the count's accuracy and the bureau's credibility as a statistical agency, Trump's memo, like the administration's other census efforts, largely flew under the radar, frequently sidelined by other controversies.

At a press conference in July, hours after the release of a memo calling for the unprecedented exclusion of unauthorized immigrants from the apportionment counts, not a single reporter asked Trump a question about the directive.

Weeks later, federal courts began declaring the memo unlawful and in some of the cases, unconstitutional as well. After the Supreme Court agreed to squeeze in a hearing for the Trump administration's appeal last fall, though, the high court's conservative majority ruled it was too early to weigh in.

In the end, timing and bureaucracy thwarted Trump's plans to alter the latest state population counts. The administration tried to pressure the Census Bureau to prematurely end quality checks, which were delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. But career civil servants postponed releasing the first set of census results after unearthing incomplete and duplicate responses.

As the inauguration of President Biden drew closer, another reality was setting in that made Trump's apportionment plan practically impossible. The Census Bureau could only come up with reliable numbers for a fraction of the unauthorized immigrant population in the U.S.

Still, even during its final days in office, the administration did not give up on trying to get state-by-state figures of unauthorized immigrants and other noncitizens. A last-minute push by the Trump-appointed Census Bureau director, Steven Dillingham — as well as two controversial appointees, Nathaniel Cogley and Benjamin Overholt — sparked whistleblower complaints about demands to produce "statistically indefensible" data, and Dillingham ultimately resigned.

Without a citizenship or immigration status question on the 2020 census forms, government records the Trump administration directed the bureau to use could only generate a state-by-state count of unauthorized immigrants in detention centers.

For the rest of the population, the bureau could produce estimates. But the methods it would have to use are saddled with "difficult-to-verify assumptions" and could "introduce substantial imprecision" to the census results, top career officials warned in a March 2020 memo.

"It is our professional judgement that these methods produce estimates of the undocumented foreign-born population at the state level that could inform policy makers," but they may not be usable when reapportioning House seats because they require the use of statistical sampling, which is not allowed, wrote John Abowd, the bureau's chief scientist, and Victoria Velkoff, associate director of the bureau's demographic programs.

The bureau has also warned, for decades, that using the national head count to identify unauthorized immigrants could undermine public trust in the federal statistical agency. That, in turn, could exacerbate historical undercounts of immigrants and people of color and reduce their areas' share of census-guided federal funding.

"We realize that our job would be made still harder ... if we had an image of being an investigative unit," Leo Estrada, who was serving as a special assistant to the bureau's deputy director, told NPR in 1980 in response to FAIR's first apportionment lawsuit.

Producing figures of unauthorized immigrants should be a "job for some other agency," Estrada said.

The bureau has shelved the Trump administration's project for creating unauthorized immigrant counts. But that work could play a role in the ongoing lawsuit by the state of Alabama and U.S. Rep. Mo Brooks, a Republican from that state who voted against certifying Biden's victory in the 2020 election and told crowds at a rally before the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol that it was the day for "taking down names and kicking ass."

Biden's executive order has restored the longstanding policy of including all residents regardless of immigration status in apportionment counts. But Brooks and the office of Alabama State Attorney General Steve Marshall are still trying to convince U.S. District Judge R. David Proctor to order unauthorized immigrants to be left out.

The future of "we the people"

For Conner, FAIR's first executive director, it's long past time to end this fight.

More than four decades after helping to launch FAIR's campaign, Conner says he has since come to recognize the long ties many unauthorized immigrants have to the U.S.

"When you say 'we the people of the United States,' you have to include them," Conner says.

Now a woodworker based in Nashville, Tenn., Conner condemns the Trump administration's immigration enforcement for not focusing on deterring employers from hiring unauthorized workers.

"For this administration to take up the census lawsuit after they have subverted any effort to recognize the implicit invitation for immigrants to come undocumented to this country to work, to live," Conner says, "I can only understand it as a pure expression of racism and evil. And yet I have to own I took this same position 40 years ago."

FAIR, however, remains committed to changing who is counted in apportionment and obtaining numbers of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S.

"You want to have as much data as possible about the fiscal, environmental and societal impacts of immigration," says Stein, FAIR's president.

Stein acknowledges the stakes of bringing this issue before the highest court in the land. If the justices declared that reapportioning House seats and electoral votes without unauthorized immigrants is unconstitutional, FAIR would have to resort to advocating for a constitutional amendment, which Stein calls a "very heavy lift."

But the Trump administration left office with no definitive Supreme Court ruling on its plan to alter counts that, according to the Constitution, must include the "whole number of persons in each state."

That leaves the door open for Alabama's lawsuit and any future legal challenges to test their limits in the courts. And as planning ramps up for the 2030 census, it leaves behind a lingering question: How much further could FAIR's campaign go if another president in line with its ambitions enters the White House?

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.