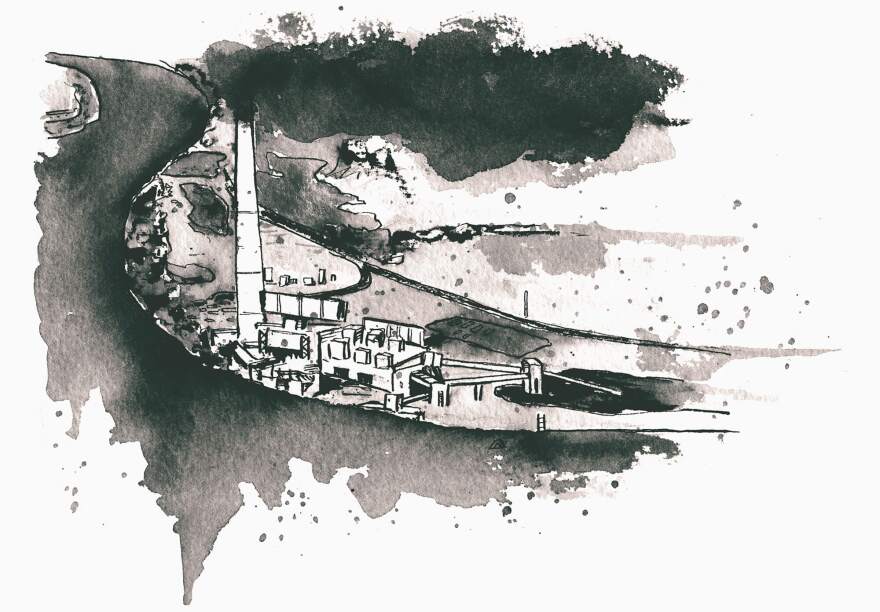

The R.E. Burger coal-fired power plant’s final day ended, appropriately enough, in a cloud of black smoke and dust. From 1944 to 2011, the plant generated power, fumes and ash in the Ohio River Valley. It was one of dozens of coal and steel plants dotting the banks of the river, which for years has ranked among the nation’s most heavily polluted.

Then, on July 29, 2016, following a series of detonations that echoed across the Ohio, the boiler house at the base of the smokestack crumpled amid flickers of flame. The 854-foot-tall tower toppled sideways, struck ground and sent up puffs of dirt and brick. In footage posted online, the noise is drowned out by the sound of whooping and applause from thousands of people who’d gathered in lawn chairs along the riverbanks to watch.

The demolition of the R.E. Burger plant is symbolic of one of the most significant energy transitions in U.S. history. Two out of every five power plants that burned coal to make electricity in 2010 were shut down by 2018, largely replaced by natural gas power plants — the result of a decade-long fracking rush.

Few places have been quite as dramatically impacted as the northern Ohio River Valley, where shale well pads now lace the backroads of Appalachia’s former coal towns. Twenty-nine new gas-fired power plants are planned or under construction in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia alone.

Historically, coal and steel marched hand in hand — coal powered the steel mills that built the Rust Belt. Now, with natural gas, industry can make a different kind of raw material, one that drillers and the International Energy Agency say represents the future of global demand for oil and gas: plastics.

The vast majority of petrochemical production in the United States has always taken place along the Gulf Coast. But drawn by low-priced shale gas from fracking in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia, the petrochemical industry is increasingly eyeing the Ohio River Valley as a manufacturing corridor.

Oil giants are banking on plastics and petrochemicals to keep the fossil fuel industry expanding amid rising concern over climate change.

“Unlike refining, and ultimately unlike oil, which will see a moment when the growth will stop, we actually don’t anticipate that with petrochemicals,” Andrew Brown, upstream director for Royal Dutch Shell, told the San Antonio Express-News last year.

Industry analysts have projected the region could support as many as seven additional plants on a similar scale. The American Chemistry Council has tallied $36 billion in potential investment that could be tied to an Ohio River Valley petrochemical and plastic manufacturing industry.

Projects currently on the drawing board would unleash a flood of newly manufactured plastic from the region, using raw materials from fracked shale gas wells. Shell’s $6 billion ethane cracker in Potter Township in Beaver County, Pa., is projected to create roughly 3.5 billion pounds of polyethylene pellets each year. A similar volume is expected from a second plant proposed just over an hour’s drive south in Dilles Bottom, Ohio — to be built on the site of the razed R.E. Burger coal-fired power plant.

Green-lighting petrochemical projects along the Ohio River could bring new industrial vitality to a region that’s been hard hit by the slow decline of American coal and steel. It could also bring a host of issues. Shell’s cracker will be permitted to pump out 522 tons of volatile organic compounds into the air — nearly double the amount that the state’s current largest source, U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works, produced in 2014 (the most recent year available).

State permits also allow Shell to produce 2.25 million tons of carbon dioxide. That means this one plant, with its 600 jobs, will wield a carbon footprint one-third the size of Pittsburgh (population 301,000).

Plastic made on the banks of the Ohio is likely to reach the farthest corners of the globe. Shale Crescent USA, an industry group, projects that half of the plastic made on the Ohio would be shipped to Asia for use there. Only 9% of the plastic ever made has been recycled, with the vast majority of the rest winding up in landfills or oceans.

Into The Bloodstream

On a hillside overlooking Shell’s petrochemical plant in Monaca, Pa., new houses are going up in a subdevelopment tucked behind a shopping mall. “Like the view?” a sign posted by builder Ryan Homes reads. “Stop by our model home to find out how it can be yours!”

From the cul-de-sac, you can watch Shell build its ethane cracker in the valley. Three dozen towering cranes, including one of the world’s tallest, are assisting in assembling the plant. The cracker’s components, like a 285-foot-tall quench tower, are often so massive that they wouldn’t fit on roads and had to be shipped in by barge.

Shell’s plant hasn’t yet started pumping out plastics. It’s expected to be fully operational in the early 2020s. The cracker will heat ethane — a natural gas liquid abundant in the region’s shale wells — at temperatures so high that the molecule cracks and becomes ethylene. Ethylene can be transformed into polyethylene, the plastic familiar to consumers from food packaging, milk jugs and garden furniture.

Old-timers will tell you the air around Pittsburgh used to be so thick with sooty particles that city workers would change into new shirts at lunch. These days, the skies look much clearer. That doesn’t mean all of the dangers have dissipated.

“What comes out of a well pad, what comes out of a compressor station, what comes out of an ethane cracker plant are pretty similar,” Dr. Ned Ketyer said at a community forum in St. Clairsville, Ohio. Ketyer is a pediatrician who serves on the board of Physicians for Social Responsibility Pennsylvania.

“It’s important to note that almost all of these are invisible,” including the chemical fumes and tiny particulate matter from gas and plastics operations, Ketyer said. “You can’t see it, but it’s so small that it gets into the deepest part of the lungs and can get absorbed into the bloodstream.”

At the forum organized by Concerned Ohio River Residents, an environmental group, Ketyer played video footage recorded in August by environmental nonprofit Earthworks with a special FLIR camera at a compressor station and at two different drilling sites.

“Everything looks nice and peaceful, nice and clean, nothing going on here,” he said. But in the FLIR camera footage, “you can see the air filling up with emissions.”

The Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project took the data from Shell’s air pollution permits and, assuming that the plant would actually pump out half as much as its permits allowed, ran the numbers on how high emissions exposure would reach, Ketyer said. The report found that a cancer treatment center next to the subdevelopment would expose those breathing outside to an “extreme” level of five hazardous air pollutants. The mall itself would see emissions four-and-a-half times higher than the cancer center.

Studies have found that those fumes can make people ill.

“We’ve known for decades that certain pollution causes certain symptoms,” said Ketyer, listing as examples headaches, shortness of breath, impaired thinking and changes in blood pressure. “So right here, Beaver Valley Mall, this is 1 mile directly downwind from the cracker plant,” he continued. “It’s going to be inhospitable, if not uninhabitable, in my opinion.”

“Everybody’s Dying”

About an hour east, Donora, Pa., is home to a historical society and museum emblazoned with the words: “Clean Air Started Here.”

There is also a striking number of empty buildings. About 4,600 people call Donora home, according to census data, roughly a third as many as a century ago. More than 8,000 people used to work at the steelworks here, owned by American Steel and Wire Co., a U.S. Steel subsidiary. Roughly half worked at the plant’s zinc works, used to galvanize wire, nails and other steel products.

The air pollution was anything but invisible back then — and it was never darker than a series of fall days in 1948. Just before Halloween, a thick cloud of smog, known as the “Donora death fog,” settled over the town. More than 20 people died within days of respiratory and other problems and more than 6,000 people became ill.

Today, most of the survivors of the smog have passed away, according to Brian Charlton, curator of the Donora Historical Society, but in 2009, filmmakers interviewed 25 people who’d been there. The survivors described how grit and ash from the plant routinely darkened the skies over the town but then, for several days straight, the smoke all seemed to stay trapped in the town.

“I worked at the telephone office,” Alice Uhriniak told the filmmakers. “We always had smoke in Donora, from the mills and everything, and it was dark. But when I got into the office, and the girls that had worked nighttime, they said, ‘Hurry up, get your set on, everybody’s dying.’”

Firefighters went through town with oxygen tanks and the town’s pharmacy scrambled to supply cough medications, while a community center became an improvised morgue.

“I told ‘em the best thing they could do at that particular time was to get out of town,” Dr. William Rongaus, a Donora physician, told the documentarians. “I had a good idea that just the poisonous gases were coming out of the Donora Zinc Works.”

Workers inside the plant who spent too much time breathing high levels of smoke dubbed their symptoms the “zinc shakes,” Charlton explained. “They would say, well you couldn’t take that environment for more than two or three hours, but their attitude was such that, ‘But we could defeat that’…It is this very tough attitude; we can take anything.”

According to later investigations, the smoke, which carried hydrogen fluoride, sulfur compounds and carbon monoxide, could cause health problems if you inhaled too much at a time.

The week of the “Donora death fog,” an unusually prolonged weather pattern left the fumes trapped in the Monongahela River Valley. There was a temperature inversion, Charlton said. “That’s the thing that really cause[d] the deaths.”

It’s an incident that seems burned in the memories of environmentalists. Because the Ohio River Valley is also prone to inversion events, they say, there’s a risk that the less visible pollution from ethane crackers could accumulate in the air. Residents often ask about inversions, too, “because that is their daily experience, they’re aware of what it feels like to be in that situation,” said Megan Hunter, an attorney with Fair Shake Environmental Legal Services.

In January, Fair Shake challenged a state air permit for the cracker proposed at the old R.E. Burger site, arguing that the state failed to properly account for the risks of air inversions.

“It’s right there in the valley,” she added, referring to the proposed cracker plant and to the town of Moundsville, West Virginia, which is directly across the Ohio River. “They’re both low and on the river itself.”

History Repeats

Officials in the Trump administration say that promoting new petrochemical and plastics projects in the Ohio River Valley can help the shale gas industry by expanding the market for “natural gas liquids,” which can command far higher prices than the methane gas that’s sold to burn for heat and electricity.

“What we need to do is increase the demand for the natural gas and especially the wet portion of the natural gas that we’re producing in this region,” Steven Winberg, assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Energy, said at a petrochemical industry conference hosted by the West Virginia Manufacturers Association in April. “And that’s going to be done through the domestic ethane crackers and the strong export market that we see for the products coming out of these crackers, for the plastics and resin.”

That plan would tie the Ohio River Valley’s economic fate to the natural gas industry, which — unlike coal and steel — has become notorious for its rapid booms and busts. Right now, counties in the shale “sweet spots” around the Ohio river hum with trucks on the highways, green compressor stations pumping fracked gas through pipelines, and the stream of deliveries to Shell’s cracker.

Reports produced by industry groups predict plastics and petrochemical projects could support 101,000 jobs in Appalachia (though a closer look shows that three-quarters of those potential jobs fall into the “indirect” and “induced” categories, not jobs at the new plants).

But shale drilling’s economic foundation could prove to be as brittle as the shale itself. Over the past decade, while horizontal drilling and fracking have unleashed enormous volumes of natural gas and the natural gas liquids prized by plastics manufacturers, drillers have frequently found themselves deep in debt, as the supply glut drove prices low.

A growing amount of that debt is expected to come due soon, analysts say. The Wall Street Journal reported in August that, from July to December, drillers will have to pay off $9 billion in debt, and that number will rise to $137 billion between 2020 and 2022. That spells risk for companies counting on a supply glut and low prices to continue for decades into the future.

And then there are the externalized costs. Matt Mehalik, executive director of the Breathe Project, said his Pittsburgh-based organization tallied projected health costs from the construction of three cracker plants in the Ohio River Valley, estimating from $120 million to $272 million a year nationwide. Over the 30-year lives of the plants, Mehalik projected, those health costs would reach $3.6 to $8.1 billion, including nearly $1 billion in Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located, and $1.4 billion in Beaver County, where the Shell plant is being built.

The economics left some concerned that history could repeat itself.

“Look what coal left this area. Not very much,” said Steven Zann, of Wheeling, West Virginia, who formerly worked at an aluminum plant. Zann was skeptical about the claim that the plastics industry could fill the shoes that steel left empty, in terms of jobs. “That’s why they’re always exaggerating the amount of employment it will create,” he said. “It’s not really going to be that. It’s not going to be the new steel.”

The Donora steelworks employed 8,000 workers at its height and supported virtually an entire town of 14,000. After construction ends, the Shell cracker will employ 600 in Monaca, a town of 5,500 — and that number includes engineers and other highly skilled workers expected to come from outside Monaca.

Fighting Cancer Valley

Driving Route 7 along the Ohio River near Bev Reed’s hometown brings you past power plants and a coal stockpile so tall that locals call it Murray’s mountain, after Murray Energy’s founder Bob Murray. Head north, and Route 7 will bring you just shy of Little Blue Run, the largest coal ash impoundment in the country, which spans the West Virginia/Pennsylvania border.

Drive south, and you’ll pass the old R.E. Burger site, where land is being cleared to pave the way for the cracker, and past the expanding Blue Racer Natrium complex, where shale gas is separated from the liquids prized by the plastics industry.

In June, Pittsburgh’s mayor announced that the Steel City would commit to getting 100% of its power from renewable energy within 16 years. Environmental groups warn that pursuing a petrochemical buildout in the surrounding region would undo the climate benefits from that shift.

Some of those born and raised in the Ohio River Valley, like Reed, have begun organizing to fight the arrival of the petrochemical industry.

Grassroots organizations, like the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition and the recently formed People Over Petro coalition, say they’re working to prevent a “cancer valley” in Appalachia (in a reference to the notorious “cancer alley” in Louisiana). They’ve held protests outside of industry conferences, organized meetings at public libraries and spoken on a bus tour of the valley organized by environmental groups earlier this year for reporters and policy-makers.

Reed’s family owns a bicycle shop in Bridgeport, Ohio, which opened in 1973. Up the hill from the shop, water flows from the ground around the clock, staining the concrete pavement an orange-red.

“My whole life, it’s been like this,” said Reed, 27, who also works at the shop. She described it as acid mine discharge from coal mining. “It keeps flowing down, and the river is right over there.”

Plastic itself has climate impacts at each step from the gas well to disposal, whether it is incinerated, sent to a dump (where it can “off-gas” greenhouse gases if exposed to sunlight) or may even disrupt ocean food chains, vital to the ocean’s absorption of carbon, according to a report published in May by the Center for International Environmental Law.

“We can’t deal with the plastic as it is,” said Reed, who started interning for Sierra Club after hearing about the industry’s plans for the valley, “so why would you want to make more rather than use what we already have or create more jobs in the recycling industry?”

The Ohio River Valley, like the rest of the United States, stands at a crossroads of energy and industry, facing decisions about whether to turn toward a future of renewable energy and a green jobs revolution or one of shale gas and plastics. Some might say there are clear skies ahead, regardless of direction, as the valley turns its back on coal and steel.

But a question hangs in the air, thick as smog: Can the public here in the hills and valleys along the Ohio count on decision-makers to steer around the less-visible hazards as they chart a course forward?

Sharon Kelly, a freelance writer for Belt Magazine, authored this story. She can be reached at shrnkelly68@gmail.com.

Good River: Stories of the Ohio is a series about the environment, economy, and culture of the Ohio River watershed, produced by seven nonprofit newsrooms. To see more, please visit ohiowatershed.org.