Disturbing behavior that the Dayton gunman reportedly exhibited in his youth may be detailed in law enforcement and school files so far off limits to the public, records that could shed light on whether authorities properly handled early warning signs.

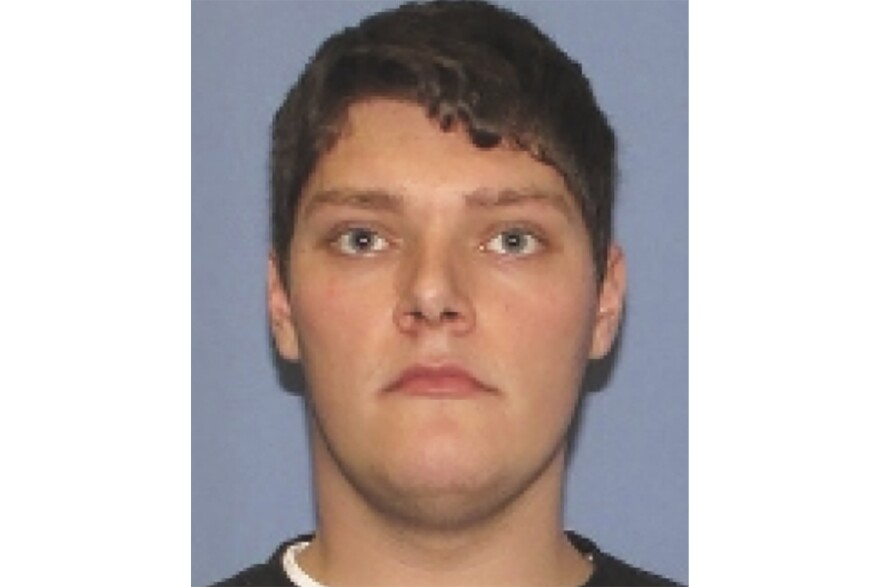

The measures used to shield 24-year-old shooter Connor Betts' school records and whatever is on his juvenile rap sheet were intended to protect people's privacy as they move from childhood into their adult lives.

But could erasing youthful bad behavior from the public record limit insights that could protect public safety? And might such measures also serve to insulate school officials from having their decisions questioned?

"Obviously, it's a very, very complex issue," said Rachael Strickland, co-chair of the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy.

Betts was killed by police after opening fire Aug. 4 in the city's crowded Oregon District entertainment area, killing nine, including his sibling, and injuring dozens more.

High school classmates have since said Betts was suspended years ago for compiling a "hit list" of fellow students he wanted to harm. Two of the classmates said that followed an earlier suspension after Betts came to school with a list of female students he wanted to sexually assault.

Police investigators say they now know that Betts had a "history of obsession with violent ideations with mass shootings and expressed a desire to commit a mass shooting." The FBI said it uncovered evidence Betts "looked into violent ideologies."

On Thursday, the Montgomery County coroner said Betts had cocaine, alcohol and an antidepressant in his system and more cocaine on his body at the time of the shooting.

Authorities have yet to publicly identify a motive, and the shielded records could provide insights into Betts' previous activities both in and out of school. Dayton police said Tuesday that they're divided on one of the more vexing questions: whether Betts intended to kill his sibling or whether her death was inadvertent.

His school district, Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Local Schools, has denied media requests for access to Betts' high school files on the grounds that such "records are generally protected by both federal and state law." News organizations, including The Associated Press, CNN, The New York Times and others, have sued.

Likewise, his juvenile police record has been expunged, which makes it off limits to the public.

Strickland said her coalition mostly focuses on protecting children from the lifelong ramifications of systematic monitoring of their social media. She said the group opposes "as a matter of principle" government surveillance of children without due process, saying it takes staff and police hours to carry out while "unfairly labeling kids."

That was part of the thinking of those who championed the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, the federal law that protects student education records, back in 1974. The act does give districts the option to release a student's records "in connection with an emergency," however.

"The mandate to Ohio schools is that we must not divulge confidential student records without clear consent from the student or parents and we have not received such consent," Liz Betz, board president for Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Local Schools, said in a statement after the shooting. "We know everyone is trying to make sense of the devastation that occurred, but we cannot bypass the law, plain and simple."

While the U.S. Department of Education holds that federal privacy protections cease upon death for those over 18, the school district is arguing that Ohio law provides broader protection.

The district's lawyer, Tabitha Justice, said that if the protections expire, as the media organizations have argued, that would mean "that the families and estates of all students who pass away, regardless of the manner of death, would be entirely without recourse with respect to those records."

In their complaint, the news outlets also argued the records can make a significant contribution to local and national debate that has followed the shooting.

"Respondents' failure to comply with their legal obligations under Ohio law should not be tolerated," the complaint said. "This community and the country at large deserve to know why this tragedy happened, what might have led to it, and what may be done to prevent future tragedies."

Michael Miller, a former longtime Franklin County prosecutor, said expungement is also a tool aimed at helping people — even well into their adulthood — avoid lifelong negative consequences for the mistakes of their past.

Lawyers sometimes offer to expunge a person's record as part of their service agreement or, if the offense is minor, some magistrates do it automatically, he said.

Miller said he puts no stock in a person's bad behavior as a teenager being a predictor of future violence.

"They're all over the map on why they do these things," he said. "It's virtually impossible to think that if we do this or that, we'll stop violence and killing people. It's been going on since the beginning of time."