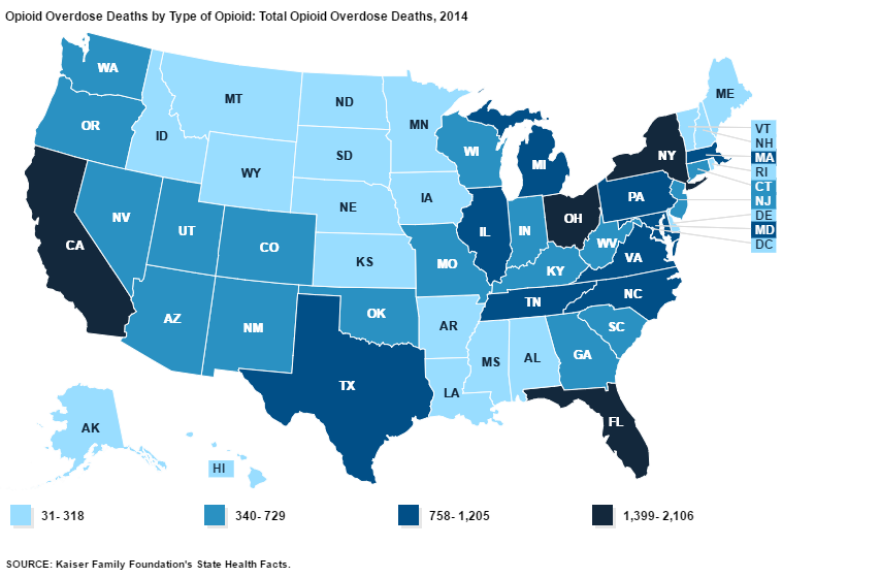

When the opioid carfentanil, an elephant tranquilizer, surfaced in Ohio last summer, it caused a public health emergency. Ohio now suffers more fatal drug overdoses from synthetic opioids than any other state in the country.

It seems carfentanil slipped through a crack in the system: a loophole in the Postal Service.

The smallest drop of carfentanil can be fatal, but it's cheap and produces a strong high. DEA special agent Rich Issacson says drug dealers buy carfentanil online and mix it with heroin to boost their profits.

But where exactly are they buying it from?

"Everything is leading towards China," Isaacson says.

Too Much Mail

Every day, almost a million pieces of mail enter into the United States from foreign postal services. And while Customs and Border Patrol agents review all incoming parcels – some 340 million per year – they estimate in 2016 they were only able to intercept about 1.5 percent of illicit drugs smuggled into the U.S.

Among those drugs are highly lethal synthetic opioids like fentanyl and carfentanil.

"It would be darn near impossible, considering the resources that we have, to check every package that comes in," Isaacson says.

Tom Ridge, the first Secretary of Homeland Security under President George W. Bush, calls this a very unique, and very large, loophole.

Ridge chairs an advocacy group called Americans for Securing All Packages. He says this loophole allows traffickers to ship illegal drugs to the U.S. with virtually no chance of getting caught or their package being intercepted.

That's because almost all foreign postal services, including China's, don't provide U.S. Customs with something called “electronic advanced data.”

"What they simply request is, who's shipping it?” Ridge says. “What's the address? Who's it going to? Describe the cargo inside? What's the weight? Tell us the number of items or pieces in it?"

If Customs and Border Control can get ahold of this data before a package arrives in the U.S., Ridge says, they can more easily identify and screen high-risk packages by targeting suspect countries or addresses.

Basically, he says, it’ll help authorities find that needle in the haystack.

"Are we saying that it will [be] 100 percent effective? No," Ridge says. "But it will dramatically, and I say substantially, reduce the risk."

A Wider Net

The system that Ridge is proposing, in large part, already exists. It just doesn't apply to all postal services.

In 2000, politicians became alarmed by shipments of the drug ecstasy coming into the U.S. from Europe. In 2002, the U.S. began requiring private carriers like UPS and FedEx to provide electronic advanced data.

Ridge says officials never anticipated that the black market would shift over to these national postal services.

"All we’re saying to you is, do the same thing with the packages coming through your postal service as you do when you send it through our private express carriers," Ridge says.

This would require compliance from 191 countries – every member of the United Postal Union.

Ridge admits it could be costly for some countries, which may lead to some resistance. But he says America is a big market, and that's not something these countries will risk losing.

Daniel Chow, an expert on international trade laws at Ohio State University, says imposing such regulations is perfectly legal, even if that means barring imports from countries who don't comply.

"The United States has a right to stop the importation of products which might be harmful to the health and safety of its citizens," Chow says.

Not everyone agrees that postal reforms are the best solution, though.

"It's always best to stem the flow at the source," says Andy Weber, former assistant Secretary of Defense in the Obama administration.

Just like the U.S. took steps to prevent the smuggling of nuclear materials, Weber says, the country could work with Chinese law enforcement to bust labs illegally producing synthetic opioids.

"It takes a global international effort,” Weber says. “No single country can deal with these transnational problems on their own.”

Stemming The Flow

For now, U.S. officials appear to prefer fixing the problem at home first.

In the previous session of Congress, Ohio Senator Rob Portman introduced the STOP Act, legislation that would require foreign postal services to provide electronic advanced data on all incoming packages. He plans to reintroduce it in the current session and says the bill has bipartisan support.

A similar, smaller pilot program is already underway by the USPS and the Department of Homeland Security.

And the most important potential advocate for this program may be President Donald Trump himself, who lists “cracking down on the loophole in the Postal Service” under his plan to combat the opioid epidemic.

The question for politicians is: When the next carfentanil comes through the mail, will authorities have the tools to stop it at the door?