After last week's shooting in Parkland, Fla., calls to arm teachers and school personnel have intensified. Both President Trump and the National Rifle Association argued this week that enabling school officials to shoot back could save lives and could deter potential assailants from entering a school.

Trump has clarified that he believes only those "adept" at using firearms should be armed, not all teachers.

Teachers are already carrying concealed guns in a handful of states, including Ohio. Officials who support concealed carry for teachers say they're not just handing out guns but carefully considering who and how they should carry. Ohio has invested thousands in training.

But many educators are uncomfortable with the idea, and worry that it could put students in further harm and deter people from entering the field of teaching, which is already facing shortages.

Ohio: 'I'm not gonna just go around and just hand guns out.'

At one training session to teach best practices in the small town of Rittman, Ohio, more than a dozen teachers stood in a line poised with guns in hand.

They were there as part of the FASTER program funded by the Buckeye Firearms Foundation. The state is also kicking in $175,000 dollars over the next two years.

For the past five years, FASTER has trained more than 1,300 teachers and staff across 12 states. Chris Cerino is a former police officer and law enforcement trainer who prepares teachers and staff in case of an active shooter.

"We teach them about target and backstop," Cerino says, "We give them good marksmanship skills. We talk to them about closing the distances and using cover. And we also talk to them about not shooting when they shouldn't or can't."

In Ohio, any school board can give permission to carry a firearm into normally gun-free schools. Those decisions are often made behind closed doors because they're part of a district's confidential safety plan.

The Buckeye Firearms Foundation's Jim Irvine says it's not just teachers with guns, it's principals, nurses, and maintenance people. And he says it's strictly voluntary.

"No one should ever be forced to carry a gun," Irvine says. "It's something you have got to want to do because if you don't want to do it, you're not going to embrace it with the right mindset and the right attitude to do it properly."

That mindset includes the possibility that children could be injured in crossfire or that the active shooter could be one of the teacher's own students.

On day two, trainer Andrew Blubaugh is showing the group how to use a small window on a classroom door to check for a threat and how to restrain the shooter if he's caught.

"What's great about you guys is when we start talking about the element of surprise, they're not expecting a teacher," he says. "They're looking for uniformed officers. That's what they're going to be cued in on. So you have the element of surprise."

Most of those getting trained here don't want to be identified. They don't want others to know they're carrying because a shooter could target them first.

Keith Countryman, superintendent of Hicksville Schools in northwest Ohio, carries a concealed gun.

"The people I've chosen to carry," he says, "I've instructed them that are to never have the gun off their body for any reason nor have it shown for any reason unless it's needed in a threatening situation."

Following the shooting in Parkland, Fla., Countryman met with his security team to consider arming more teachers who he says are not paid extra. They decided instead to consider other measures like adding more cameras outside the building.

"I'm not gonna just go around and just hand guns out. 'Hey, go get your concealed carry and you can carry a gun here at school.' That's never gonna happen at our school."

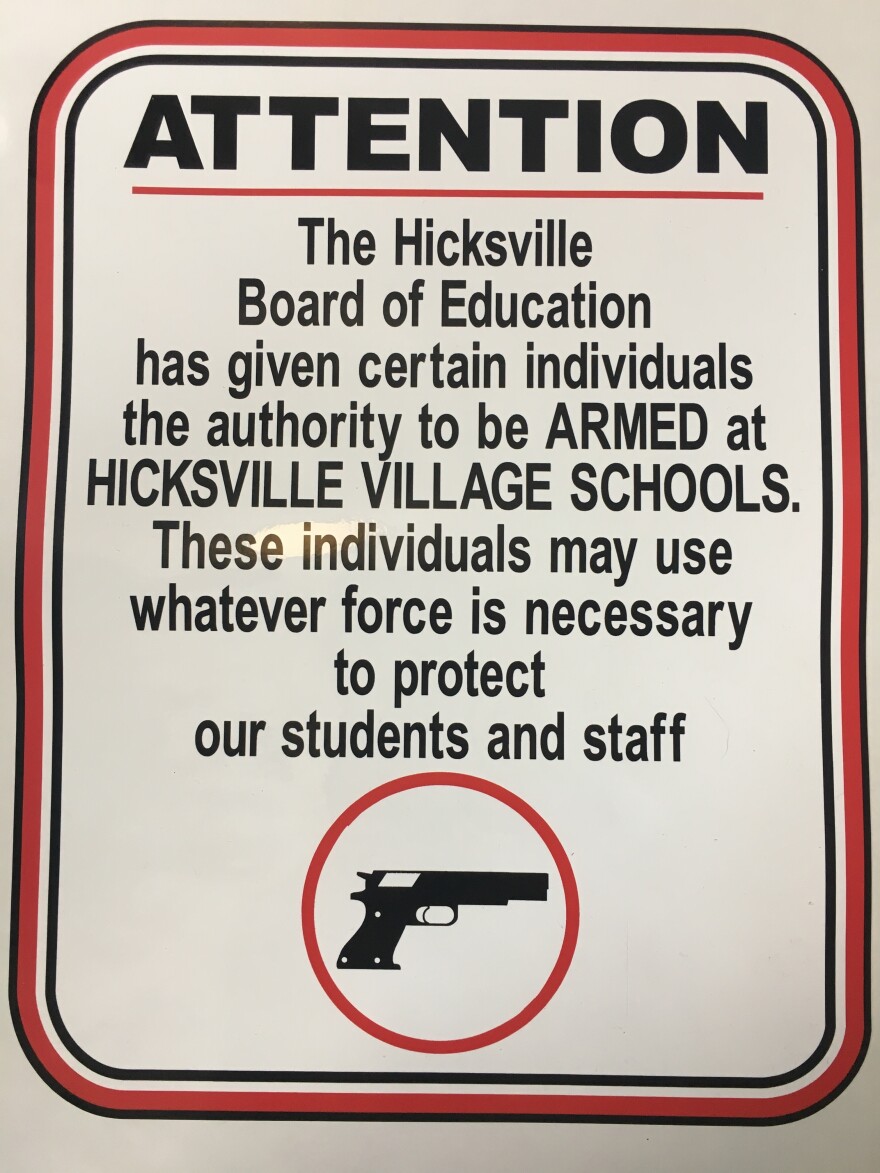

Outside Countryman's school in Defiance County is a warning sign that reads, "these individuals may use whatever force is necessary to protect our students and staff." The superintendent says he's confident if something happened anywhere in the building, they'd be able to confront the intruder within seconds.

Connecticut: 'I don't think we'll be putting guns in the hands of teachers.'

The Department of Homeland Security advises people "Run. Hide. Fight." when there's an active shooter. It's a method police departments use when training school employees, students, and increasingly, aspiring teachers.

But it's that last part — fight — that's always worried Emily Cipriano.

"I never would think: 'Here's my bag of things I bring to class to take notes'," Cipriano said. "'How am I going to use this to defend myself'?"

Cipriano is a graduate student at the University of Connecticut's education school. She wants to teach high school English one day. She's heard talk about arming teachers in the wake of the Florida shooting, but she's not interested in carrying a gun. For her, she hopes playing defense will be enough to keep her and her students safe.

"I have to believe that, ya know, with blocking the door, with using books to shield ourselves, or with setting up my classroom in a way that we're able to protect ourselves that I wouldn't have to resort to bringing anything with me to school," she said.

The president of Connecticut Citizens Defense League, a gun rights group, said there are teachers in Connecticut who want to carry a gun, but none would speak publicly about it. He also declined to be interviewed for this story.

But former teacher Rene Roselle said requiring teachers to carry a gun, would cause many to leave the profession.

"If we got to the point where we're arming teachers, then we would see people leave in a great amount," said Roselle, who now trains teachers as part of UConn's education school. She said guns should be the last thing being put into classrooms.

"If we're often not giving teachers the pencils and the papers that they need to be able to have a classroom," she said, "I don't think we'll be putting guns in the hands of teachers."

Richard Schwab is an education professor at UConn who trains school leaders. He said teachers should be armed, but not with a weapon.

"I think what we arm teachers with is knowledge," he said, adding that teachers should be prepared for school shootings, but using a gun shouldn't be part of that preparation.

"We could never prepare every teacher for every social ill," Schwab said. "We really ask a lot of our teachers. Is this one more thing? Yes. Is it the breaking point for teachers and people who want to become teachers? I don't think it is."

However, teacher shortages have been a problem for almost a decade. Many have been leaving the profession faster than they can be replaced. Enrollment in teacher preparation programs has been declining nearly every year since 2009, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

But Schwab said it's other factors — like increased attention on tests and less classroom freedom — that's driving teachers away. Possibly giving their lives for their students, isn't one of them.

"This is part of life today," he said. "Unfortunately we've had a number of experiences like this in our nation's schools. But we all have to deal with this, and we all can't hide in our homes."

Twenty-three-year-old Emily Cipriano agreed. Having grown up in a post-Columbine world, she's always been aware of school violence.

"There are so many different roles that teachers already play," she said. "I understand that this now is a huge role — you're essentially saying you're here to save a student's life. But I just think that's something we've always considered."

For Cipriano, school shootings are another part of the ever-growing list of things that teachers are asked to handle.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.