From the outside, Melania Trump looks like a woman in over her tastefully balayaged head. At public events, she rarely speaks, but assumes the rictus smolder — like a model who has just spotted a lion over the photographer's shoulder — that inspired a thousand #freemelania signs.

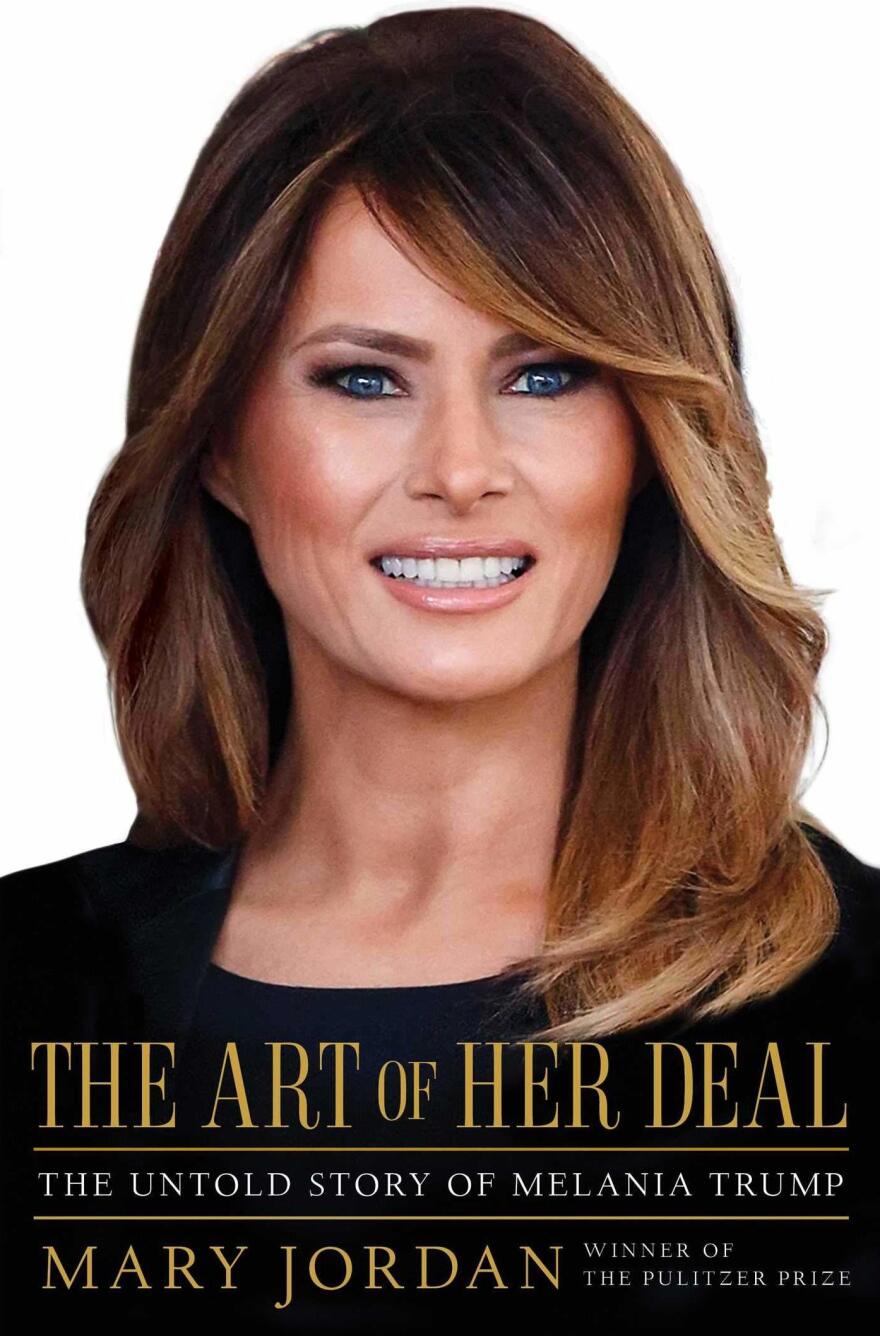

A new, scrupulously reported biography by Washington Post reporter Mary Jordan counters this perception, arguing that the first lady is not a pawn but a player, an accessory in the second as much as the first sense, and a woman able to get what she wants from one of the most powerful and transparently vain men in the world. The book is called The Art of Her Deal.

For this book, Jordan interviewed more than a hundred people, including Melania's Slovenian childhood acquaintances, staff members at Donald Trump's properties, players in the New York and Paris modeling world, and one-time Trump insiders like Chris Christie, Roger Stone and Anthony Scaramucci. She also spoke briefly to the first lady herself in the course of her reporting on the 2016 election. The result is a convincing case that those "who dismiss her as nothing more than an accessory do not understand her or her influence."

Make no mistake: Beauty is the first line in the job description. As Women's Wear Daily reported, Melania was asked in 2005 whether she would be with Donald Trump if he were not rich. "If I weren't beautiful," she replied, "do you think he'd be with me?" That stinging, cynical answer seemed to capture the essence of their exchange: money for beauty, beauty for money.

But in the years since, Melania has had to offer much more than her looks: She has endured a presidential campaign, the humiliations of Stormy Daniels and the Access Hollywood tape, and the daily demands of life in the White House.

Throughout these trials, Jordan characterizes Melania as a canny operator who believed "she had more to gain by standing by her husband than walking away." Jordan writes that after Trump was accused of infidelity and assault, Melania used the fact that he needed her public loyalty and presence in Washington to negotiate a better prenuptial agreement. Melania referred to this process as "taking care of Barron." Jordan reports that she was worried that their son Barron would not be treated as well as Trump's other children. (As Jordan points out, this was perhaps for good reason — Trump has at least once seemed to forget Barron was his, saying of Melania at a 2019 press briefing, "She's got a son.")

Melania has also influenced key policy decisions, mostly having to do with children: She pushed back against child separation at the border and advocated for harsher rules about marketing e-cigarettes to minors.

In the course of her reporting, Jordan finds that Donald Trump is not the only mythmaker in the family. She investigates, for instance, Melania's suggestion that she speaks — in addition to English and Slovenian — French, Italian and German. Jordan concludes that, like Melania's claim to have graduated from university in Slovenia, that section of her CV is likely fabricated or at least seriously exaggerated.

But The Art of Her Dealoffers few scoops in the conventional sense; its major contribution is merely the insistence that Melania is a real person with complicated motivations. This point should be obvious: Isn't everybody, in and out of the White House, complex, striving, conflicted, out for something? The flattening effect of political discourse, the special insipidity of the first lady role, and Melania's own particular remoteness have allowed us either to forget that she has an inner life, or to imagine her as an elegant prisoner.

Women in public life, from Hillary Clinton to Princess Diana, have a way of crystallizing attitudes about women more broadly. Melania speaks rarely and haltingly, and her face expresses emotion only through the narrowing and widening of flame-blue eyes. When she speaks, the planes of her face remain utterly undisturbed. Because of this ruthless blankness, she is better suited than almost any other woman in public to be a projecting screen. Which makes it worth asking: What is it in us that prefers a captive to a collaborator?

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA5NTM4MTIyMDE0MTg3NDc2MTVlZjdmNQ001))