In Washington, D.C., a stone's throw from the White House, the U.S. Capitol and the Supreme Court, there's an oasis from the high-power, high-stress world of politicians, lobbyists and lawyers.

Founded on the Washington Channel in 1977 and nestled at the intersection of the Anacostia and Potomac rivers, Gangplank Marina is a laid-back community of about 150 boat-dwellers who care less about your professional pedigree than about the beer you're bringing to happy hour.

For decades, Gangplankers lived in a quiet quadrant with a salty twist. A Washington Post article from 1983 described life on the channel as a "sun-soaked Margaritaville."

The gritty but sleepy neighborhood — a mix of brutalist government buildings, modernist residences and a few restaurants beloved as much for their existence as their menus — felt devoid of bustle. And the southwest waterfront remained set apart and difficult to access, despite the total overhaul of Southwest D.C. decades earlier — an urban renewal project that displaced 23,000 mostly black residents between the early 1950s and the early 1970s.

In other words, you could pretty much always find a parking spot.

When I moved to Gangplank in 2017, all of that was about to change.

In October of that year, the first phase of the $2.5 billion mixed-use development called District Wharf opened on the channel's shore. After years of planning and construction, it turned the sparsely developed corridor of the city into a shiny entertainment district overnight. The Wharf also assumed ownership of Gangplank Marina — renaming it Wharf Marina, though most residents don't call it that.

With three concert venues, rooftop bars and pools, apartments under 550-square-feet that rent for about $2,500 a month and even an on-trend restaurant devoted to toast, the District Wharf is a stark contrast to the motley crew of sailboats and barges at the marina.

At the time, my husband and I were housesitting for his uncle, who owns Speakeasy,a 43-foot floating home at the Gangplank.

With the community on the cusp of massive change, I wanted to create a visual time capsule before the full transformation took place. So I started making portraits of our neighbors on their boats, mostly using a medium format film camera with 12 frames on each roll. (I filled in with a digital camera at times.)

I felt a harmony between film — the timelessness, the quality, the process and the mix of unpredictability and simplicity — and the choice to live aboard a boat. Yes, you might have to walk on a slippery dock to fill your boat's tank with water in the winter, but you'll also watch the sunset every night.

During portrait sessions, I wanted to find out how neighbors made it to Gangplank, why they chose to leave behind "the hard" (or "land," in sailor speak) and what they treasured about this way of life.

I hoped that my images would capture the breeziness of Gangplank and the contagious spark of the "don't worry, be happy" attitude that's an antidote to the busyness felt elsewhere in D.C. People make time to chat by the communal recycling bins; they ask to borrow bouillon cubes on the community email group; they organize a weekly Sunday morning breakfast affectionately called "Captain's coffee."

People arrived at Gangplank, widely noted as the largest liveaboard community on the East Coast, via different paths — in search of cheaper rent, through a party invite or a newspaper ad. And for many of them, the community felt like coming home.

"You leave your profession at the gate," says Roger Thiel, who after 30 years of living aboard is the marina's most-tenured resident. "It's possible to live near a congressman or a member of the House of Representatives for a year without knowing it."

"It's a little bit like you're living in a nature preserve. You see the baby ducklings go out in the spring," says Dick Marchi, who lives on the barge Our Island with his wife, Laneyse Hooks, who has grown everything from herbs to corn on her rooftop garden.

The feeling of being connected to nature came up often. "The weather, the rhythms of the water, the sunsets, the fish, the birds — there are so many cycles going on around us at any moment," says Curtis Sloan, who moved to Gangplank from Takoma Park, Md. "I was certainly surprised the first time a fish started nibbling at the things growing on the bottom of our boat. That little tapping noise was wild to hear!"

But the word that surfaced the most frequently was "community."

"I thought I had made it in life when I drove out of my suburban garage and a few miles down the road into my underground office building — never getting wet, hot or cold from the experience," says Gary Blumenthal of his life in the Virginia suburbs. "Now I check the weather constantly and ride my bicycle year-round, getting wet, cold and hot. We know nearly all our neighbors and spend huge amounts of quality time with them. Instead of having made it in life, this community enables one to experience life."

In 2013, Darryl Madden's boat caught fire because of a mechanical error during routine spring maintenance. He lost everything.

"By the time the fire [was put] out, the community had completely rallied around me," he remembers. "They had gone out, got me clothes, toothpaste, food for the next couple of days. They had made arrangements for me to stay aboard a boat so I had a place to live."

Despite the trauma of losing everything, he decided to buy a new boat and stay at Gangplank. "I not only loved the community, but I loved me in this community," Madden says.

Kelly Simon, who has lived on several boats since moving to the marina in 2014, says the most interesting thing to her about Gangplank is the diversity of the residents.

"Everybody hangs out across generations, and it doesn't matter if I'm 40 and we're hanging out with someone who is 60," says Simon.

![Melissa Ascher and Kelly Simon aboard Lucky Star<em>. "</em>Lucky represents [Kelly's] Irish background," says Ascher. "And then the star is my background, like the Star of David, because I'm Jewish. And then it's also a Madonna song, so it just kind of all worked out."](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/797b6f4/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3389x1349+0+0/resize/880x350!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2019%2F08%2F05%2Fharlan_gangplank_marina_wharf_luckystar_custom-e730c310d419b5ef64414c989cc4058ea2586521.jpg)

The marina operates a lot like a floating trailer park — you own your boat but not the water underneath it. And that water has become prime real estate.

As the desirability of the location increases, so do the prices of the boats there.

Another factor in why vessels at Gangplank sell for a premium is that there are a limited number of docking spaces (known as slips), currently 88. To live there, you essentially have to buy a boat that's already in the marina from its current owner, who then transfers their liveaboard rights.

Despite rising costs, boats at the marina still tend to be more affordable than condos or homes in the D.C. area.

Jason Kopp says he paid about $50,000 for his first boat at Gangplank in 2007. Now, he thinks a boat of similar quality would go for twice as much. "Just because people want to live here."

There have been plenty of changes for liveaboards since the redevelopment — losing a dedicated parking lot, eventual slip fee hikes for legacy residents (boat owners have to pay monthly slip fees to management) — but one of the biggest changes is relocating from the decades-old wooden docks to new concrete docks a few hundred feet down the channel.

In general, residents are finding the silver lining: safer dock conditions, rising boat values, more than a few restaurants to choose from and satisfaction that the Washington Channel is getting much deserved attention.

"Even though we have these two fantastic rivers in the city, there hasn't been a lot of great public access to them," says Kopp, who says people have been surprised when he tells them he lives on a boat in D.C.

Why? People didn't realize there were rivers in the city.

"If there's one really positive thing about the development, it's that there's better access that is being created for the general public to the water," he says.

But for some, the impact of the changes, especially the move, is harder to predict.

"I am wary of the changes now and wary of losing some of that core of community as we move to modern and more antiseptic living," says Thiel, the Gangplanker with a 30-year tenure. "The funkiness of it — I like things that are old and funky or adapted."

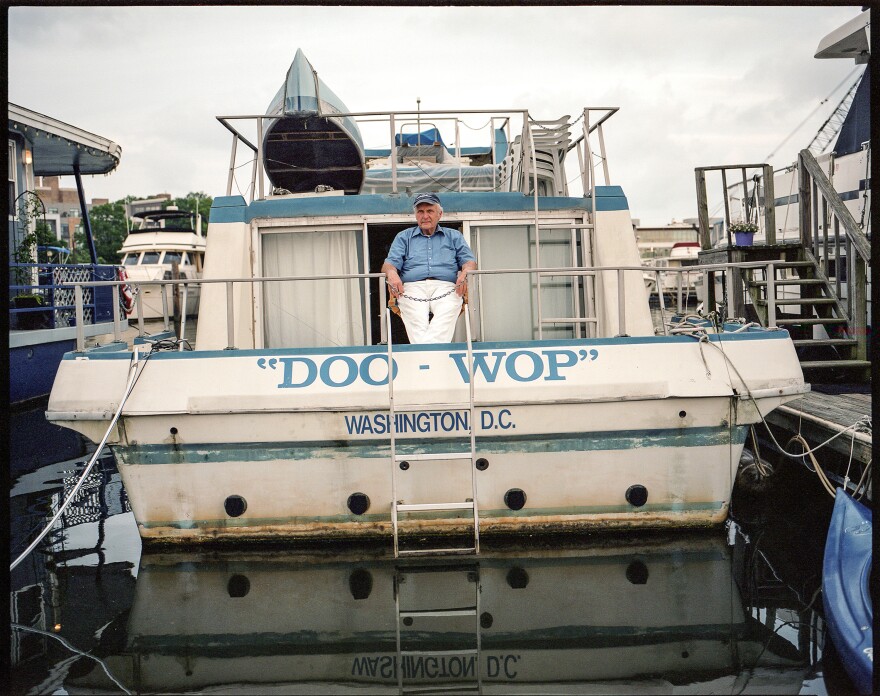

Thiel is a man who loves history. His boat is named Doo-Wop, he wrote a book about World War II planes and he doesn't use email — other residents from Gangplank regularly send notes on his behalf.

This past February, all the houseboats relocated to new concrete docks. The last morning that we had access to the legacy docks before they were demolished, I ran into Thiel walking on the slippery, wooden walkway while feeding the ducks, a daily ritual. It was an odd feeling: All the slips were empty but one — where the boat Act of Grace remained.

It would be easy to feel homesick for the familiar patina and rituals and rhythms of a long-dwelled-in place. But something Thiel said to me in an interview months earlier reminded me that for him, as for many of us, home ismore about the folks we call neighbors than the physical place we live.

"If it wasn't for the camaraderie of the Gangplank people," Thiel said, "I would have left D.C. 20 years ago."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA5NTM4MTIyMDE0MTg3NDc2MTVlZjdmNQ001))