Regina Bateson doesn't look like a gambler, but that's what she's become — in the world of politics.

She just left her tenure-track job at MIT to run for Congress back home, in Northern California. She's a Democrat with zero campaign experience. And she needs to unseat the Republican incumbent in her solidly Republican district.

She's fighting this unlikely fight because technology — in the form of an online platform called Crowdpac.com — made her believe it's possible.

Bateson had a good life. She was a political science professor at MIT. She was a mom — just had twins in fact. And then, the November 2016 election happened. Bateson recalls lying on a rug, infants in her arms, and crying. She says she was thinking about what Donald Trump's victory meant for her kids: "I have three boys. They're all little boys. And I don't want them to grow up in a world where bullying is the norm."

That night she was in shock. Then, over the coming days and weeks, she started to feel a higher calling. She took a good long look around and told herself: "This is a time when we all have to stand up, and have the biggest impact that we can. We each need to do the biggest thing that we can."

The biggest thing. It's a thought a lot of people are having.

Bateson started eyeing politics back home. She's a Democrat from California's 4th Congressional District — a stunningly beautiful district that includes Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park. It went to Trump. Yet she's convinced the incumbent, Republican Rep. Tom McClintock, can be defeated because, she says, "he's so out of touch with his constituents."

Take the environment. According to a Yale survey, 69 percent of the district believes climate change is happening. And in a town hall meeting, McClintock denied it was happening. "The climate changes rather dramatically over the millennium," he said. "There is a great debate right now over the climate."

A man shouted back, "No there isn't!"

Bateson was sitting in the bleachers, her blood boiling. In 2008, McClintock won office by a tiny margin. But he's been winning with landslides ever since. She has a theory about why: The Democrats who've tried to unseat him didn't raise enough money. She looked into the records and saw that candidates raised only about $9,700 to $105,000. That's chump change.

While issues and party affiliation matter, money also matters. A campaign is like a startup. You need to pump it with cash.

And that is where the Internet begins to factor into this story.

Bateson wanted to find ways to raise money for Democrats in her district. So she Googled terms like "Kickstarter politics." And she got back a site called Crowdpac.com.

Like other sites, Crowdpac (which is nonpartisan), ranks candidates on issues and lets you donate. Unlike others, Crowdpac also lets you explore the idea of running for office, without having to commit.

It's a simple idea that's worked to grow marketplaces and competition outside of politics. If you're thinking about creating a dream juicer, there are plenty of places to go to raise money, like Kickstarter. But if you think you may want to run for office — be a congressperson — until recently there hadn't been a place online where you could test the waters financially.

Bateson recalls sitting at her computer the night of the town hall and feeling seduced by the language on Crowdpac. "They used the word 'explore,' " she says. "If you're exploring running for office, you should make a site and see how it turns out. See what you think. Maybe share it with some people for feedback."

Bateson made a page for herself. It went viral in her district. She got more than $4,000 in the first 24 hours. In just over a month, she hit her goal of $20,000. And emboldened by this strange realization — that people she doesn't even know are willing to give her campaign money — the former professor decided to leave her job and become Candidate Bateson.

"If someone had said to me you need to make a decision today — that you're definitively, definitely running — I would have said no," she says.

She and her family have moved backed to the 4th District — and she's just wrapped up her own town hall in Granite Bay, Calif. "This is so exhausting," she admits. She's not used to this lifestyle.

It's an uphill battle. A senior Democratic Party strategist says "crazier things have happened," but it's a "tough district" and others in California offer "more fertile ground" for the party.

Jon Huey, campaign manager for Rep. McClintock's reelection, writes in an email to NPR that "every race in the country is going to be hotly contested because of the temper of the times." That said, Huey continues, "I think [Bateson's] in for a big surprise if she thinks the close 2008 race is predictive of the 2018 race." In 2008, McClintock was brand new to the district and, despite being outspent by the other Republican in the primary (his $900,000 to the challenger's $6.4 million), he prevailed. Since then, following redistricting, the 4th District includes some of the most conservative counties in the state.

Bateson has an ambitious goal — to raise $3.5 million — and hopes that the small amounts she's been able to raise online help convince bigger donors and her party's gatekeepers (the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee) that her district is competitive after all.

Around the country, a handful of political newbies are doing what Bateson did — including Republicans, third-party hopefuls and even two other Democrats in her district. The San Francisco-based startup makes money by taking a cut from the donations.

There's a 10-1 ratio of Democrats to Republicans seeking support on Crowdpac. CEO Steve Hilton says, "It seems to me the energy in politics is there," on the progressive side. It could also be a network effect — friends telling friends.

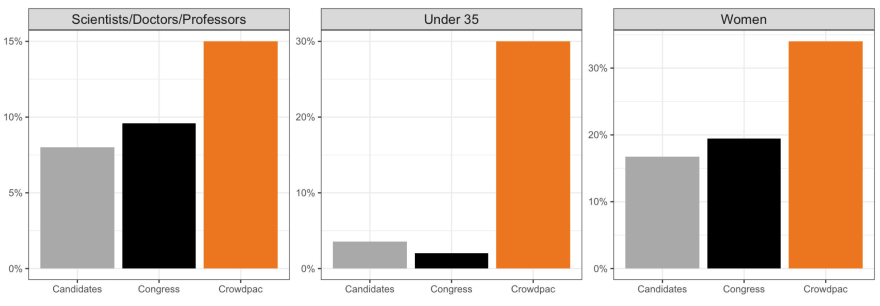

In other respects, the platform is seeing substantial diversity — with disproportionately high use among women candidates, people under 35, and non-lawyers (scientists, doctors and professors).

Hilton himself is neither a Democrat nor a Republican. A former senior adviser to U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron, Hilton moved to Silicon Valley in recent years and considers himself so independent, he's made up his own label: "a positive populist." He says the reason there's so much turmoil in politics is "the traditional party structure is a failure and the parties have totally let down half the country."

He hopes to see a "big political realignment" one day. And he says this crowdfunding platform — which lets political outsiders explore first, commit later — is a practical way the tech sector can help bring new blood into the tired business of politics.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA5NTM4MTIyMDE0MTg3NDc2MTVlZjdmNQ001))