In 1977, a bold new way to watch television launched in Columbus. Warner Cable would now offer an unheard-of 30 channels. But even more impressive was the remote control that let viewers interact with local shows in real-time. The new service was called QUBE.

One WOSU listener wrote into Curious Cbus to ask "How did QUBE start in Columbus and what happened to it?"

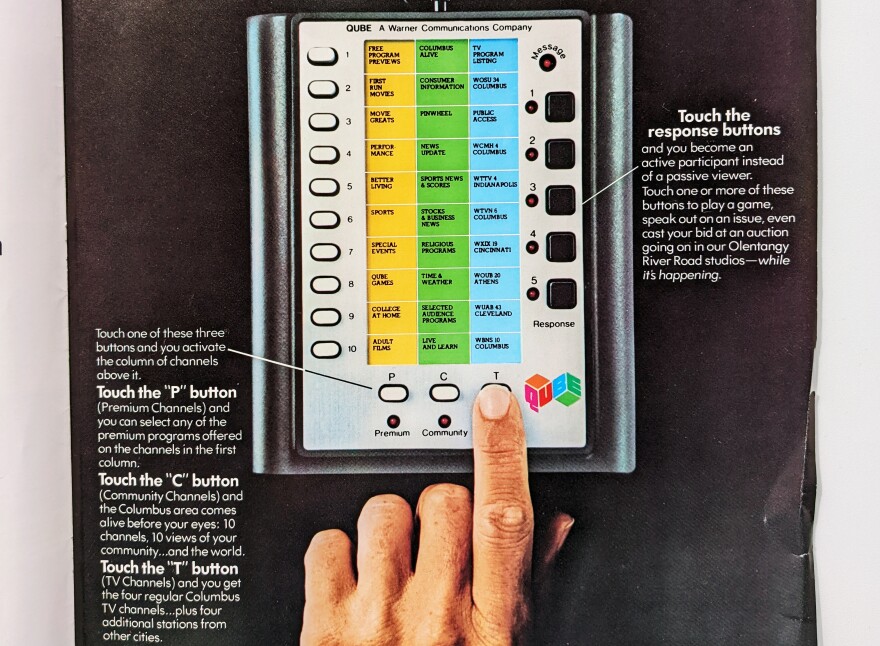

Forty-five years ago, most TV viewers could expect 3 or 4 channels with an antenna. Cable television, which was first created to reach rural homes, opened up new possibilities. That included more channels, better reception, and in the case of QUBE, a console that gave subscribers the ability to "talk back" to their television set.

Years before the widespread use of home computers or the internet, QUBE created a truly novel form of two-way communication.

In the Spring of 1977, Warner Cable started hiring staff in Columbus. Employees got to work installing large banks of computers and a new production studio at their headquarters at 1201 Olentangy River Road.

Columbus has a long history of being a test market for new products and may have been chosen in the case because of its proximity to New York City and Warner executives.

Carol Williams joined QUBE as part of the marketing team in 1977 and worked in franchising and programming during her tenure there. She described QUBE as a highly collaborative workplace with a young, mission-driven staff.

“Nobody knew for sure what we were getting ourselves into," Williams said. "All we knew was that it was going to be very well funded and we were there to showcase the opportunity of having an audience participate in the programming that they saw on TV.”

QUBE launched on December 1, 1977. For a fee of about ten dollars a month, subscribers got access to a new line-up of local interactive programs.

Flippos Magic Circus was a kid's show hosted by Bob Marvin, a.k.a. Flippo the Clown. Marvin worked for decades as Flippo, hosting children's shows and movies on WBNS.

Jim Jaeger, who worked on QUBE's tech crew from 1977 to 1984, said that when Warner was looking for talent, they wanted the top TV personality in Columbus.

"When they found out it was a clown in a blue suit covered with pompoms, they freaked out," Jaeger said. "But they hired him away from Channel 10."

During his show, Flippo would ask viewers to participate in games, offer their opinions, and answer trivia questions.

Another popular show was Talent Search where—decades before American Idol or America’s Got Talent—QUBE customers voted for local acts.

The flagship daily news program called Columbus Alive! would poll viewers on the issues of the day. On one notable occasion, then-Mayor Tom Moody appeared on the show after the Blizzard of 1978 and got feedback from the audience on the quality of snow removal in the city.

The teen talk show called Columbus Goes Banannaz featured celebrity interviews and one of the most popular shows was Soap Scoop, which gave a daily synopsis of the plot lines of all the network soap operas.

QUBE also created the first version of pay-per-view with their set of Premium channels. This included a channel of adult-rated films that courted controversy at the time.

Jaeger said when viewers watched a movie, concert, or sporting event for a set amount of time, the computers would log it and bill the account.

"Back then, it might be a dollar for a movie or five or ten dollars for a premium event like the Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran fight," Jaeger said.

QUBE eventually expanded to other markets across the country, and that put the sustainability of the business to the test.

Williams said that the expansion of QUBE affected the programming budget.

"It became apparent that we couldn't spend at the level we were spending and so as more markets were added and the dollars had to be distributed, everything started notching down a little bit in terms of local programming," Williams said.

Additionally, maintaining all the computers and production studios was a very expensive operation.

"It cost a lot of money to run that place," Jaeger said. "We had three studios with full tech crews... We'd have half-a-dozen engineers maintaining the place [and] a bunch of I.T. people running the computers, 24-7."

Another factor in the decline was that Warner Communications made an ill-fated investment in the Atari video game system, which had losses of over $500 million in a 1983 industry crash.

Eventually, it became clear that the cable service would continue but the local programming—and the interactivity—would not.

The QUBE experiment ended in 1984. While it only lasted seven years, it's hard to call it a failure. Beyond the technological advancements, former Qube employees went on to be pioneers in the television industry at places such as MTV and QVC.

Williams said she thinks of QUBE’s legacy as a test tube for innovation.

"I feel as though Qube was a brilliant step in communications... That we really pushed the envelope and helped establish a wide variety of new opportunities," said Williams.

One part of QUBE that still lives on today is its’ children’s channel called Pinwheel. It offered twelve hours a day of commercial-free content aimed at a pre-K audience. That concept would evolve to become a mainstay on cable television across the county after a name change to Nickelodeon.

Both Jaeger and Williams describe QUBE as the best place they ever worked. Years later, former employees continue to stay in touch and get together, most recently at the 40-year reunion.

"During the heyday, people worked unbelievable hours and became incredibly close," Williams said. "We were family."

This story is part of WOSU’s Curious Cbus project. If you have a question about the history or future of our region, submit your idea below.